Reverse engineering the license key generation of an old RPG game

Table of Contents

Preface

During my exam period this semester, I did everything I could to avoid preparing. Included trying to find 0-days in a router, sleeping late, and watching YouTube. I recently discovered a channel, that has content, I really enjoy, super concise, straight to the point, and educational. The channel is Nathan Baggs. The channel has videos on reverse engineering mainly older games. One sentence stuck with me “I spent a lot of time as a kid playing Age of Empires, and now I want to go back and see how it works”, I wondered … what games did I play a lot as a kid? Or perhaps some game I couldn’t play? I had bought a game at a garage sale once, that I never got working, because the license key had already been used, that shouldn’t stop me I thought!

I remembered playing the sequel to the game, but one of my favorite content creators at the time said that the game he enjoyed most in his life was this exact game. I was excited to try playing it, but alas license keys weren’t sold anymore. I went to all the local stores around me, and couldn’t find it. So, many years later, trying to avoid my exam - I wondered, could I get to play this game for the first time?

The problem

The game had less than three percent of the original code of it’s prequel and is written in C++, and normally played on Windows - looking around I was even able to find a full decompilation on GitHub of the prequel game. Now let’s go ahead and install the game!

Ah, no - we’re prompted for a name, and a CD-Key, in the format of

Ah, no - we’re prompted for a name, and a CD-Key, in the format of XXXXXX-YYYY-ZZZZZZ-XXXX-YYYYYY, I.e. 6-4-6-4-6. As we recall, this game isn’t sold anymore, so how would we acquire a license key? We could scour eBay, or we could figure out how the licensing check works, and generate our own license keys?

Reversing

I created a Windows 7 VM, installed x32dbg, and cracked open the Installer.exe in Ida on my main system.

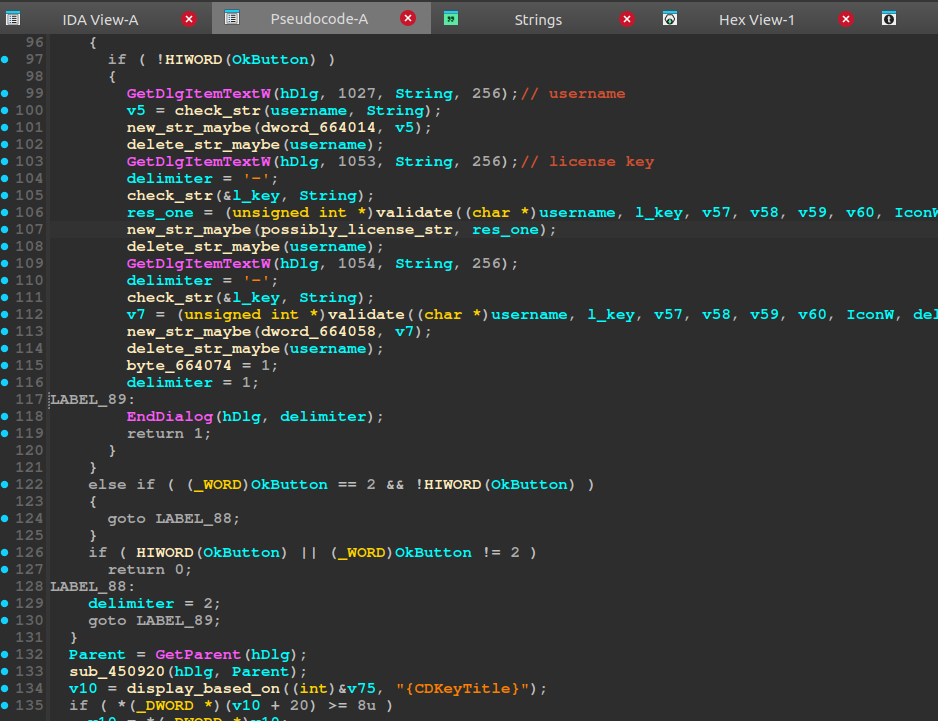

We know from running the game that there are a few things present upon start-up. A EULA, input fields asking for Name:, and CD-Key:, all present in windows. This was my first real Windows RE project, so I had to read a little bit of the Windows API documentation. I ended up with the function GetDlgItemText, which is a WIN32 function in winuser.h, that “Retrieves the title or text associated with a control in a dialog box.”. Quite quickly I found something interesting:

Analysing the validate, it seemed to find our hyphens in the CD-key, and create a license-key string without hiphens. I spent quite some time here initially, running with the debugger I could see that it was reaching, and performing operations on our license key, however the calling convention looked weird, I found out, that C++ uses the thiscall calling convention for C++ class member functions, which was a setting I could use in x32dbg - nice, I learned something new!

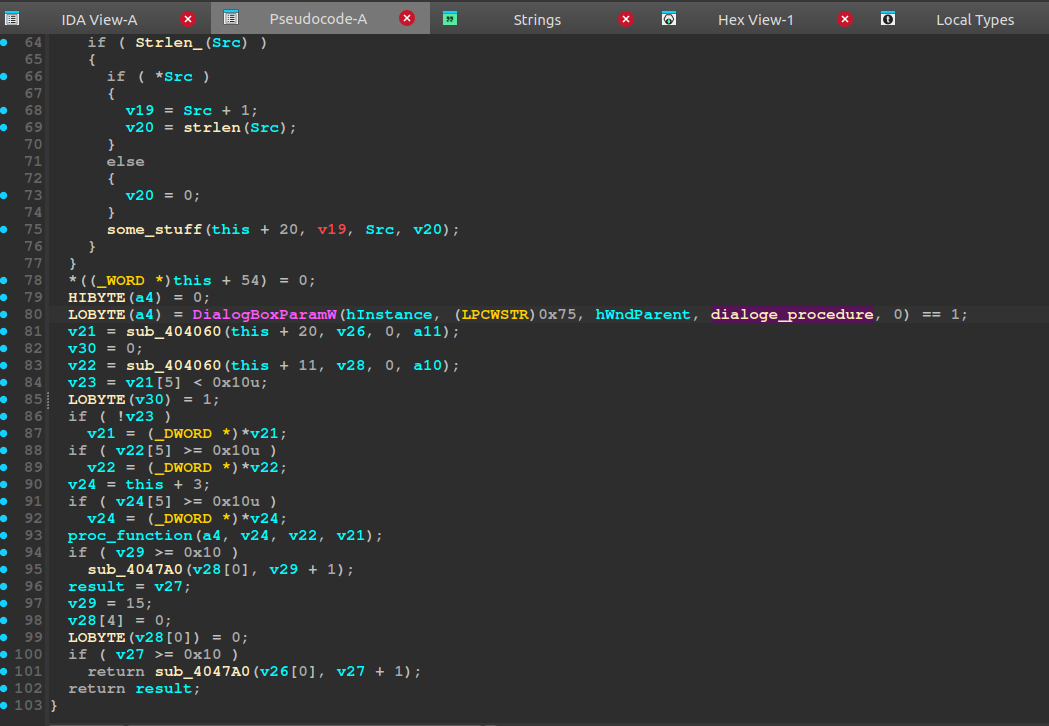

However, I couldn’t find anything that I thought looked suspicious or similar to a license key check. C++ being a nuisance, and lacking symbols I spent quite some time trying to figure out standard string functions and what they were doing. I finally came to the conclusion, that I was probably wasting time looking in this function, and that it must be doing operations on the license key somewhere else. Failing to utilize the hardware breakpoints in x32dbg to check for reads on the license key, I went back to Ida. This function I called the dialogue_procedure. It was used only once, as a proc function to the WIN32 api function DialogBoxParamW:

One specific function after this DialogBoxParamW was interesting, the proc_function (renamed later). Breaking on it, while dynamically analyzing, we see that indeed our username, and license key is passed to it. We end in a function that seems to confirm that we’ve found something interesting, just going of the strings:

Going even further:

Wow, that looks like it could be some sort of license checker. Looking in the outer function, there’s a label that seems to return gracefully without any errors, that’s probably when the license key is right. Using dynamic analysis, tracing the execution and breaking on the final test al, al instruction, we change al so that we’ll go to this label, to confirm our suspicions… It works! We get the screen where we can select an installation directory!

Neat! We try installing the game, and everything seems to work. Now I can finally play the game. However, that type of procrastination would not be good, let’s instead continue reversing! I wanted to create a license key generator, and properly understand the check implemented.

Reversing the license checker

The goal with this part is trying to understand how it roughly works, but mainly to reimplement it in Python, to generate our own keys. It would definitely be possible to instrument it all through Frida, but I wanted to do it this way.

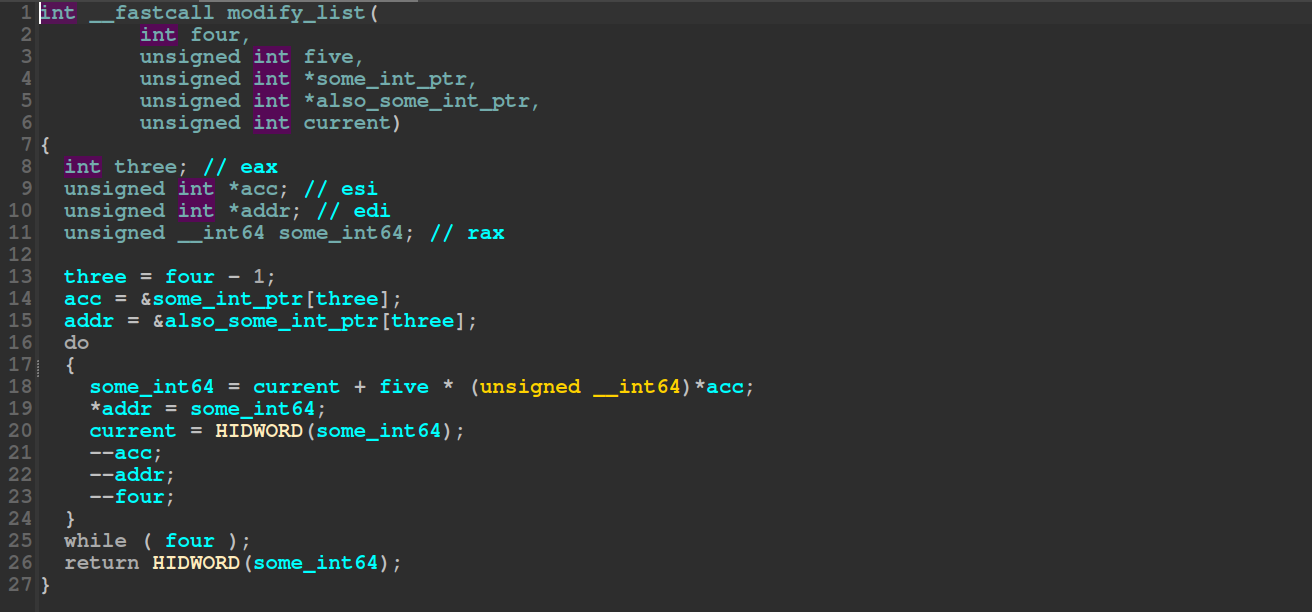

Level 1

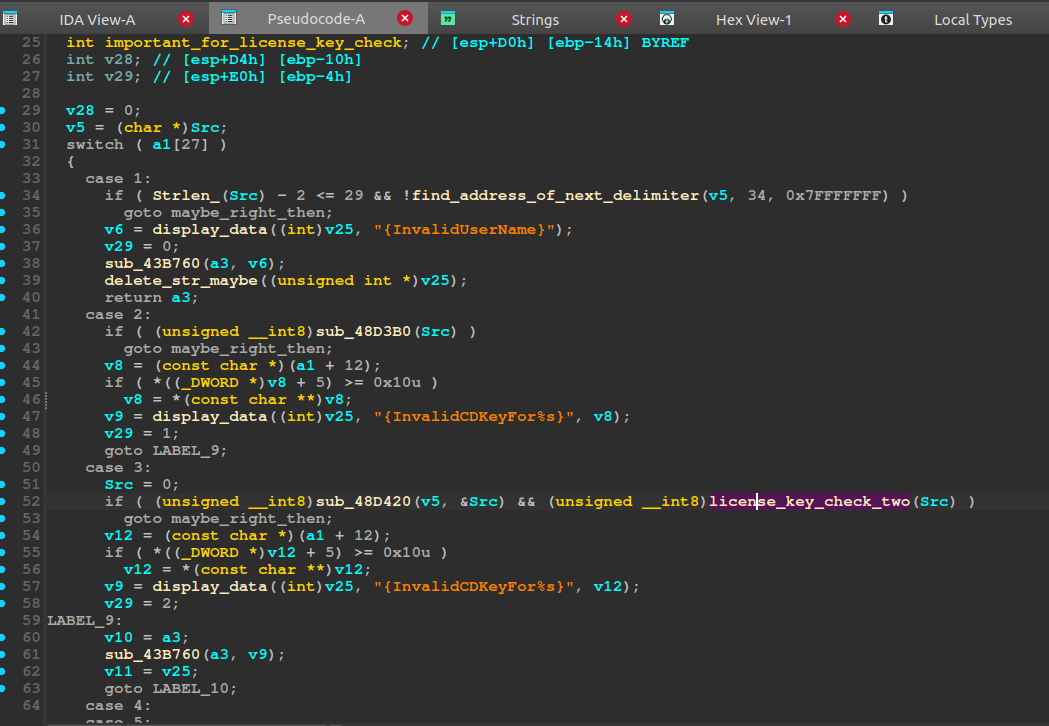

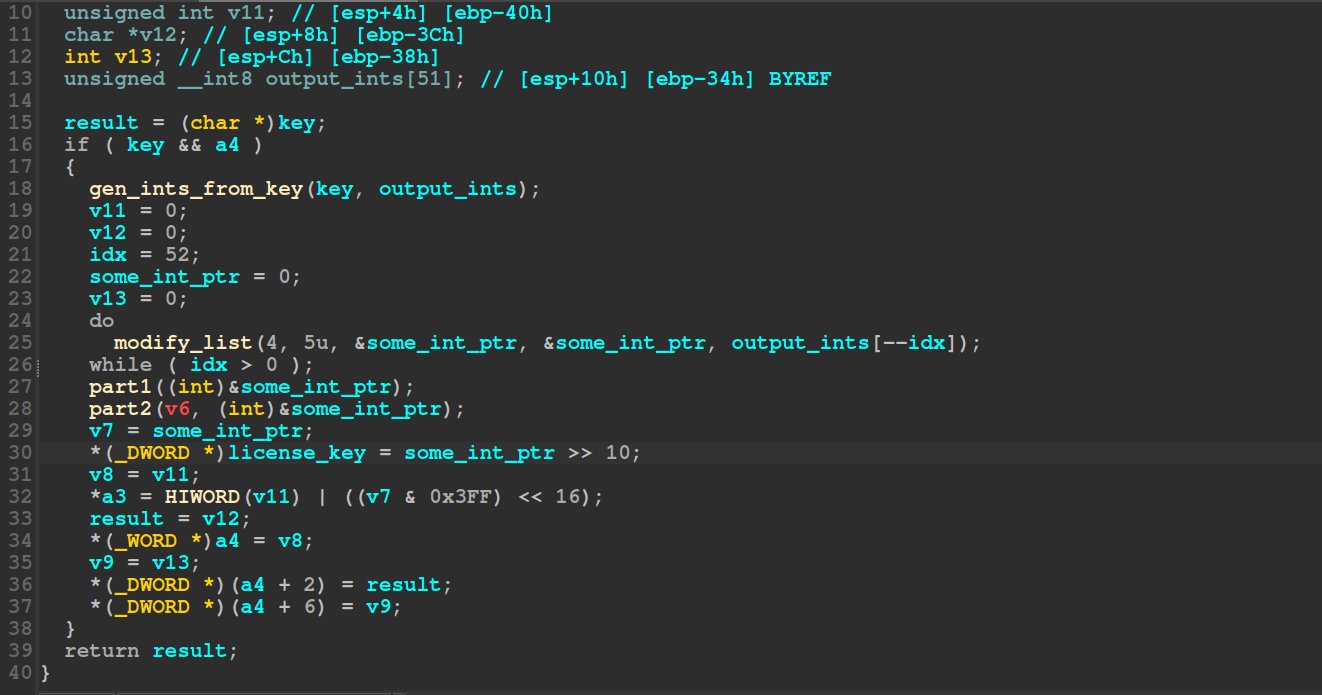

We go to the license check function that created the return value in al that we patched before. Initially it checks if the key exists, and then it calls four different functions, I refer to these respectively, in order, as level 1 through 4 - this is the real game. The outer function calls level 1 with our key, and an empty __int8 array with 52 elements. We recall that our original key has 26 characters and 52 == 26 * 2.

Let’s dive into the function.

Let’s dive into the function.

This looks pretty straight forward after some initial cleanup. The loop iterates from 0 to 0x1a, I.e. 26 times. Each iteration it calculates an offset into a lookup table based on the current character in the license key, it then generates a result and remainder and updates the output integer array. Let’s write level 1:

# Lookup table omitted

output = [0 for _ in range(52)]

remainder_offset = 33

for i in range(0, 0x1A):

result_offset = (remainder_offset + 1973) % 0x34

remainder_offset = (result_offset + 1973) % 0x34

key_i = ord(example_key_no_hiphens[i])

result = lookup[key_i] // 5

remainder = lookup[key_i] % 5

output[result_offset] = result

output[remainder_offset] = remainder

Checking with our debugger we can convince ourselves that we do get an array out that matches our Python code, neat. It looks roughly like this (dependent on the key of course), here we’ve used all A’s:

[51, 0, 51, 0, 51, 0, 51, 0, 51, 0, 51, 0, 51, 0, 51, 0, 51, 0, 51, 0, 51, 0, 51, 0, 51, 0, 51, 0, 51, 0, 51, 0, 51, 0, 51, 0, 51, 0, 51, 0, 51, 0, 51, 0, 51, 0, 51, 0, 51, 0, 51, 0]

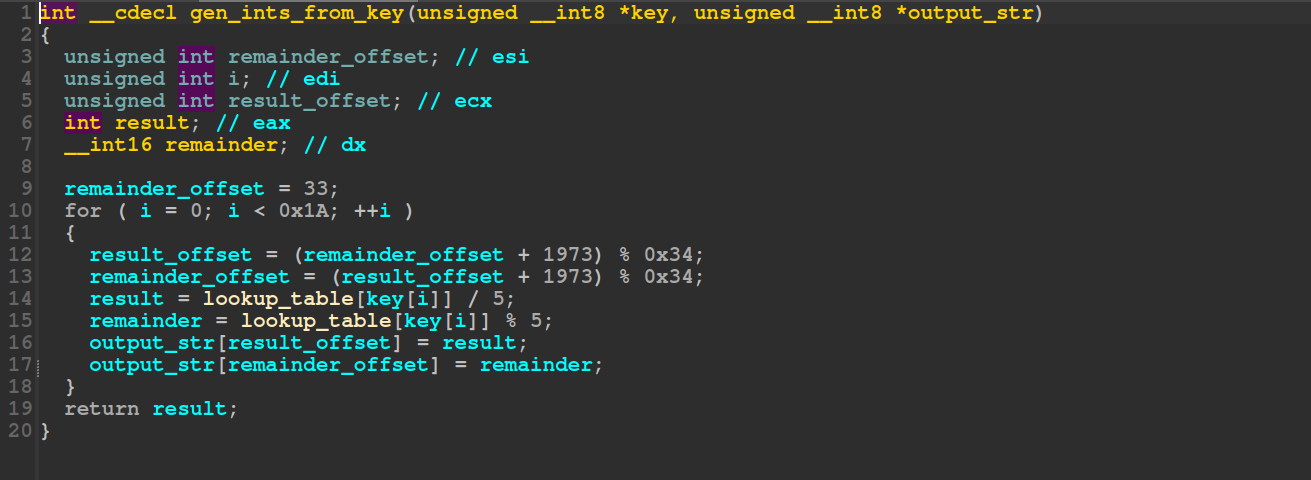

Level 2

Next we’re dealing with the modify_list, it’s called as seen in the image before, with arguments: modify_list(4, 5u, &some_int_ptr, &some_int_ptr, output_ints[--idx]), while idx > 0. Effectively iterating backwards through our integer array of 52 entries from before, let’s look at the code.

This function iterates and changes the value at

This function iterates and changes the value at addr exactly four times, however it also modifies addr. addr is an array of unsigned integers, and thus decrementing it moves the index position into addr, one down. Essentially this code creates an unsigned integer array with 4 elements. The value at each is dependent on current + five * (*acc), seems fairly simple we’ll create some python code:

idx = 52

acc = [0 for _ in range(4)]

while idx > 0:

k = 3

v = 4

idx -= 1

curr = output[idx]

while v:

value = curr + 5 * acc[k]

acc[k] = value & 0xffffffff

curr = value // (2**32)

k -= 1

v -= 1

And output matches with debugger: [0x38cbd70, 0xbbda971d, 0x3e89da05, 0x63fae0ac].

Level 3

Wow, almost done - we’re 50% there.

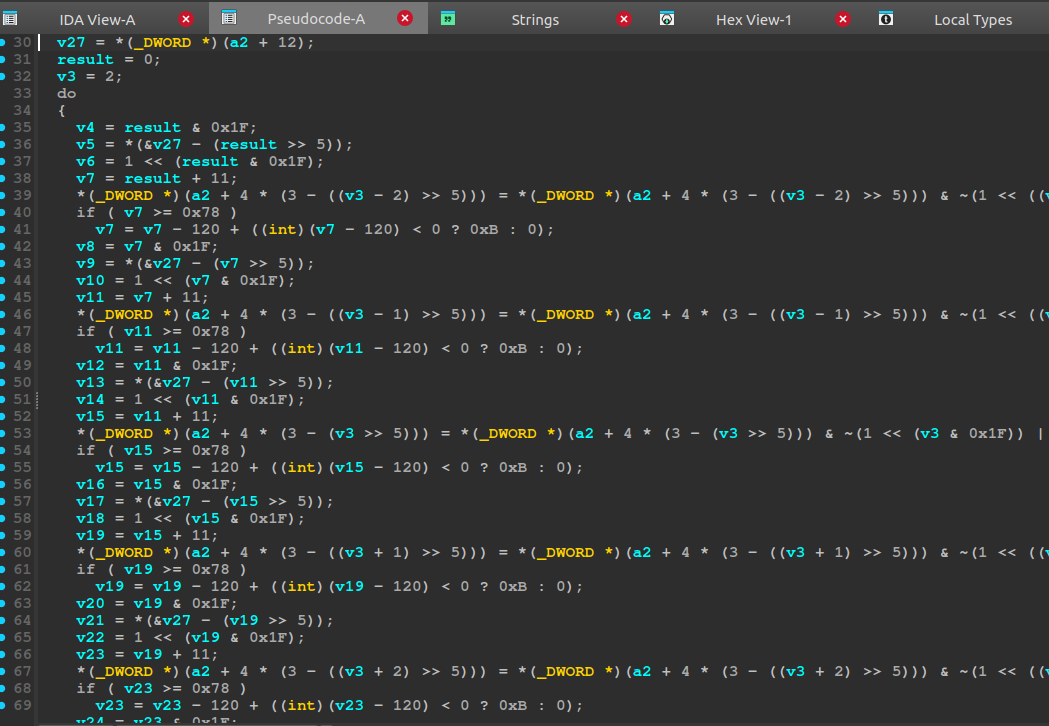

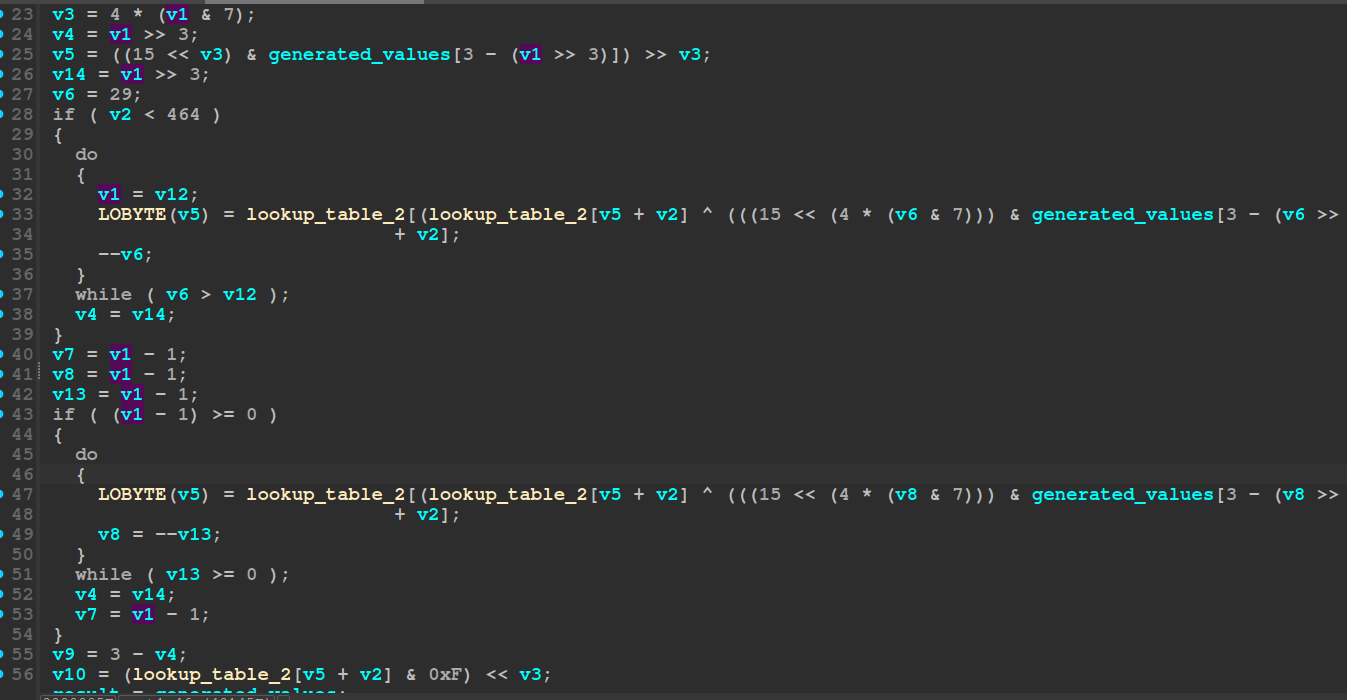

This function is a bit bigger. It now utilizes a new lookup table, XOR, bitshifts, and a bunch more. Honestly I didn’t spent too much time on it, it was fairly straightforward to just convert this to Python, and I was on to the next level. Overall this function takes the previous 4 uint array, and modifies it based on bit operations with the lookup table and some local variables that change each iteration. Neat, but looks scarier than it is.

This function is a bit bigger. It now utilizes a new lookup table, XOR, bitshifts, and a bunch more. Honestly I didn’t spent too much time on it, it was fairly straightforward to just convert this to Python, and I was on to the next level. Overall this function takes the previous 4 uint array, and modifies it based on bit operations with the lookup table and some local variables that change each iteration. Neat, but looks scarier than it is.

Level 4

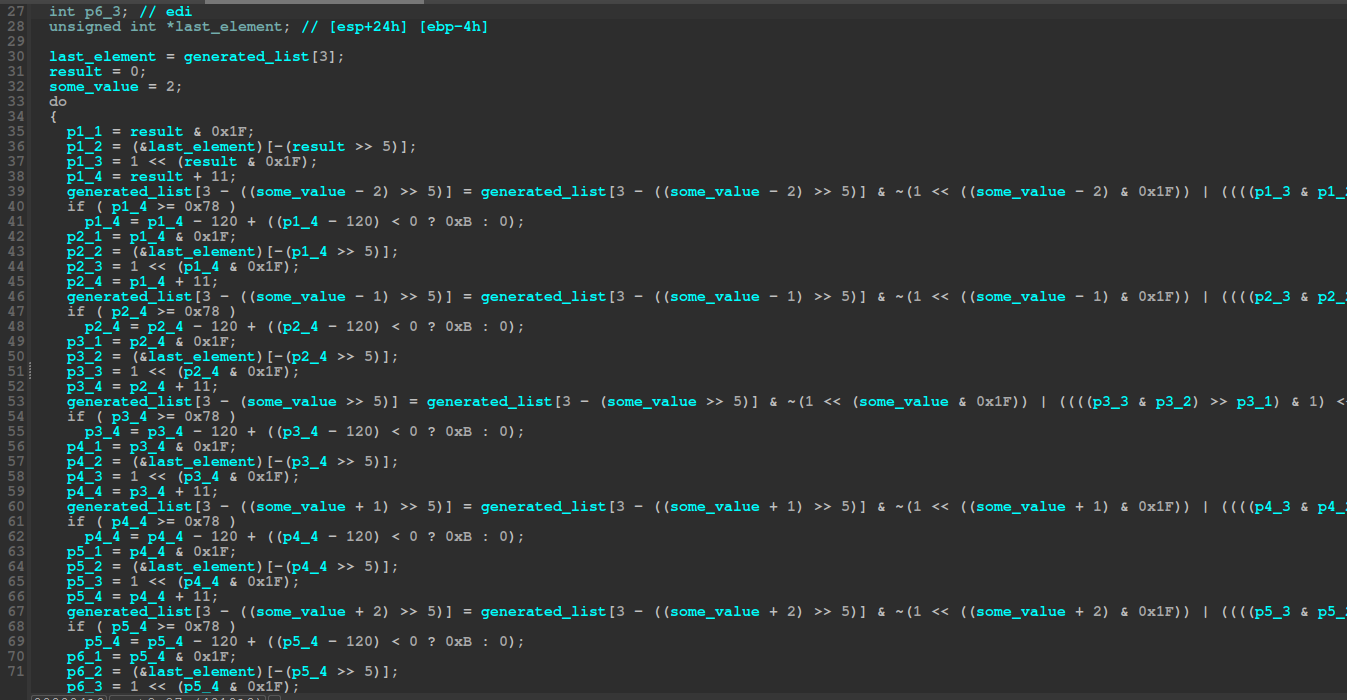

This was the final boss, the one that almost made me quit. I started of with cleaning it up in Ida, while looking a bit scary, most of this is the same done over and over for new variables, so we can probably re-implement it with a single loop.

The indexation based on

The indexation based on generated_list[3] I.e. the last_element, was weird. Implementing the code in Python as Level 3, should be simple. However I don’t get the same output. This was my initial understanding of the code:

- Get the first value (px_1) and 0x1F

- Get the second value (px_2) based on last_element, which is based on the address of generated_list’s last element, so if that list changes so should this last_element

- Get the third value (px_3) based on the initial result bitshifted and then anded with 0x1F

- Get the fourth value (px_4) based on the initial result + 11

- Update generated list based on a long sequence on operations

- If we overflow, correct and subtract

- Repeat for next parts

We can generate the following code:

def process_step(acc, first, some_value, offset):

p1 = and32(first, 0x1f)

p2 = acc[3 - rshift32(first, 5)]

p3 = lshift32(1, p1)

p4 = and32(first + 11, 0xffffffff)

idx = 3 - rshift32(some_value + offset, 5)

assert idx >= 0 and idx < 4

bit_pos = and32(some_value + offset, 0x1f)

extracted = rshift32(and32(p3, p2), p1)

bit = and32(extracted, 1)

set_mask = lshift32(bit, bit_pos)

clear_mask = not32(lshift32(1, bit_pos))

acc[idx] = or32(and32(acc[idx], clear_mask), set_mask)

if p4 >= 0x78:

p4 = ctypes.c_int32(p4).value

p4 = and32(p4 - 120 + (0xb if p4 - 120 < 0 else 0), 0xffffffff)

return p4

def part2_loop(acc):

result = 0

some_value = 2

while some_value - 2 < 0x78:

next = process_step(acc, result, some_value, -2)

next = process_step(acc, next, some_value, -1)

next = process_step(acc, next, some_value, 0)

next = process_step(acc, next, some_value, 1)

next = process_step(acc, next, some_value, 2)

next = process_step(acc, next, some_value, 3)

result = next

some_value += 6

return result

All the functions that do bit operations were added because I spent such a long time thinking about potential mistakes, I.e. 32-bit numbers, signedness, etc. that it just made me more sure that something weird was going on. Claude agreed with my implementation and on multiple occasions generated code that returned the same output based on the decompilation. However stepping through with x32dbg revealed that it was not even close. I asked around, did some more masking with 0xffffffff, and nothing helped. I began stepping through this function slowly one by one in x32dbg and comparing, however it iterates through this function a bunch of times, and figuring out exactly where it deviates while ensuring I didn’t make any mistakes was hard.

Item achieved: Hook of joy

After some time I decided to hook the application with Frida, to debug context through different points during execution. The idea was not to bypass the license check with Frida, but instead create a script that would output the values of px_1, px_2, .. px_4. The Frida script looked approximately like this:

/* Omitted for brevity, above contains p1 through p3 */

var p4 = ["0x401234", "0x40123c", "0x401243", "0x40124e"];

p4.forEach(element => {

Interceptor.attach(ptr(element), {

onEnter: function(args) {

if (this.context.eip == parseInt(p4[0])) {

console.log("p4_1 ecx", this.context.ecx);

} else if (this.context.eip == parseInt(p4[1])) {

console.log("p4_2 ebx", this.context.ebx);

} else if (this.context.eip == parseInt(p4[2])) {

console.log("p4_3 edi", this.context.edi);

} else if (this.context.eip == parseInt(p4[3])) {

console.log("p4_4 eax", this.context.eax);

console.log("-----------");

}

}

});

});

Process.enumerateModules({

onMatch: function(module) {

if (module.name == 'Installer.exe') {

console.log('[+] Found Installer.exe at ' + module.base);

}

},

onComplete: function() {}

});

These addresses were found in Ida, and based on when p4_x were set. I quickly threw this code together so it’s not very elegant. I used this to figure out were it diverged initially, which was during the first iteration of the loop specifically: mov ebx, [ebx] ; p2. which was supposed to get the value from p2 = acc[3 - rshift32(first, 5)]. I was stumped, everything else was the same, the precedence seemed to be the same, everything. After a tiny break I noticed that the values read from mov ebx, [ebx], only changed between four different values. What? The array acc is constantly modified, but there was only four different values in [ebx]. Turns out it only uses the original array, when retrieving in this part of the loop, thus the fix was copying the array and doing: p2 = original[3 - rshift32(first, 5)].

Exiting the dungeon

We finally got output matching the debugger output. However,

We still have the final part, this essentially takes the value of our array’s first element, bit shifts it to the right by 10, and saves the value. This will later be compared with

We still have the final part, this essentially takes the value of our array’s first element, bit shifts it to the right by 10, and saves the value. This will later be compared with 0x18, so our success criteria for a valid key is that this returns 0x18. We wrap all our code in a while True loop generating random keys, check if it matches for 0x18 and:

[*] Valid key found: ABK0CX-331E-5ZFFRS-I2YV-IKAQEY

[*] Valid key found: ABASCT-VBPO-3XCSB2-689I-7JLQGY

...

[*] Valid key found: ABY1O6-O62I-EBTC8F-CXNP-BCXQJG

(These are modified in the blog post such they are not valid keys, as I do not want to share the keys, even though I did not disclose which game it is.)

Conclusion

I think I passed my exam, I’m writing this blog post after the examination, and I definitely spent too much time doing other things. However, I learnt a lot about Windows reversing, and I’m finally confident in using x32dbg on somewhat straightforward PEs, it was also my first time using Frida for a real-life task, and it was a pleasure.