Preface

This blog post, and the ones following it, will be discussing how I did vulnerability research on a router - specifically the model TL-WR720N. I have never done embedded vulnerability research before this, and that might be reflected in the post. The posts will be chronological from beginning to end. Enjoy! (Also no, ChatGPT did not write this)

Getting started

Picking a target

To begin doing embedded vulnerability research, it’s quite nice to have a lot of tools. Specifically a soldering iron, multimeter, UART cable, JTAG, reflow station, etc. I however had nothing when I begun this project, and I still only have, not even, the bare essentials. Regardless I made it work, by borrowing, and biking around town to find tools I could use for free. Thanks to everyone helping me with tooling:)

The project began mid December, when I was home at my parents during Christmas vacation. During this time, I went to a thrift store near me, and picked up a router, an ethernet cable, and a power supply. The purchase set me back $4 total.

Luckily the firmware was already on the TP-Link website. This is both amazing, and a bit disappointing. This means that we won’t get to dump the firmware off the physical hardware, which could’ve been fun.

Taking it apart

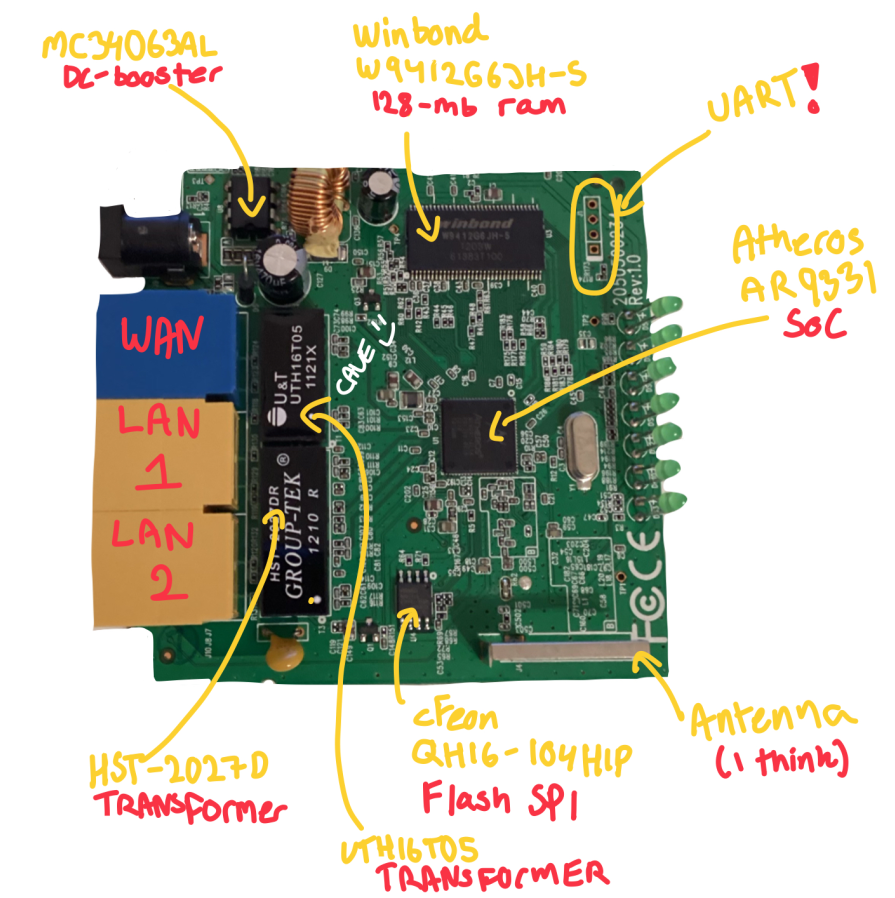

I still wanted to take the device apart. I wouldn’t be dumping the firmware, but I still might need to get UART on the device. UART stands for Universal Asynchronous Receiver/Transmitter, and is a communication protocol described by RS-232 (Recommended Standard 232). For a lot of routers this will at some point give a serial terminal. We can often run commands on those, that will help us analyze what’s happening on the system. We will look at UART in-depth in a later post regarding this project. For now however, let’s take it apart.

Let’s start by noting, that we do see the classical UART through-holes in the top right. In the middle we see the System-on-a-Chip or SOC, specifically it’s the Atheros AR9331. It’s responsible for all the same things as a CPU, but also has built-in RAM, and support for 802.11 WLAN. The CPU is a MIPS 32Kc which is a 32-bit RISC core, that is, a reduced instruction set. It has additional ram in the form of a Winbond W9412G6JH-S. Furhtermore, it houses a small mounted antenna, and lots of other interesting components.

Firmware Analysis

We start by trying to understand the firmware. In embedded systems, the firmware is stored on the flash memory chip. In our case the cFeon FLASH SPI EEPROM chip, seen on the picture above. It’s specialized software made for running on the embedded system. Let us start by running binwalk on the firmware:

$ binwalk wr720nv1-en-up.bin

DECIMAL HEXADECIMAL DESCRIPTION

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

20 0x14 IMG0 (VxWorks) header, size: 1556064

26740 0x6874 VxWorks operating system version "5.5.1" , compiled: "Jun 18 2013, 12:19:11"

26836 0x68D4 LZMA compressed data, properties: 0x6E, dictionary size: 8388608 bytes, uncompressed size: 636256 bytes

262292 0x40094 IMG0 (VxWorks) header, size: 1293792

262420 0x40114 LZMA compressed data, properties: 0x6E, dictionary size: 8388608 bytes, uncompressed size: 3645552 bytes

1253300 0x131FB4 Wind River management filesystem, compressed, 194 files

(...) Omitted for brevity

There’s a few things to address here. Let’s start from the top. We see that the description of the first element is IMG0 (VxWorks) header, size: 1556064. Then at the second element we’re given a hint that VxWorks is a type of operating system, and that it’s running version 5.5.1. We can also see that there’s apparently a file system Wind River management filesystem. Using dd if=tplinkfirmware-wr720nv1.bin of=test bs=1 skip=1253300 count=9356 we can extract some files from the file system. The dd command did not extract all the files from the file system; instead, it created a text file that contains a list of the files that exist on the system.

owowowowowowowowowowowowowowowowecommon.js

$css_help.cssT/css_main.cssb1Pcustom.js4menu.js5Dtop.htm=

AccessCtrlAccessRuleModifyHelpRpm.htmJ@AccessCtrlAccessRulesAdvHelpRpm.htm

CAccessCtrlAccessRulesHelpRpm.htm/EAccessCtrlAccessTargetsAdvHelpRpm.htm

NKDAccessCtrlAccessTargetsHelpRpm.htmNAccessCtrlHostsListsAdvHelpRpm.htm

4RpAccessCtrlHostsListsHelpRpm.htmTAccessCtrlTimeSchedAdvHelpRpm.htm$X|

AccessCtrlTimeSchedHelpRpm.htmZAssignedIpAddrListHelpRpm.htm^AutoEmailHelpRpm.htm`TBackNRestoreHelpRpm.htm

bChangeLoginPwdHelpRpm.htmd DateTimeCfgHelpRpm.htmeDdnsAddComexeHelpRpm.htm<hDdnsAddHelpRpm.htm

l DMZHelpRpm.htmo,DomainFilterHelpRpm.htm<q,DynDdnsHelpRpm.htmbuhFireWallHelpRpm.htm

xFixMapCfgHelpRpm.htm.zL2tpCfgHelpRpm.htma}LanArpBindingHelpRpm.htmLanArpBindingListHelpRpm.htm

nLLanDhcpServerHelpRpm.htmLanMacFilterHelpRpm.htm@LocalManageControlHelpRpm.htm`MacCloneCfgHelpRpm.htm

ManageControlHelpRpm.htmMiscAdvHelpRpm.htm.HMiscHelpRpm.htmfxNetworkCfgHelpRpm.htmNetworkLanCfgHelpRpm.htm

yNoipDdnsHelpRpm.htmhParentCtrlAdvHelpRpm.htmxParentCtrlHelpRpm.htm

This gives some interesting information that we can note for later. As most of these are .htm files, it’s likely that they will be endpoints in the routers web panel. Using binwalk --dd=".*" we can extract more files from the firmware. We can look at the output more in-depth.

Let’s start by addressing the first element, we were told that it was an operating system called VxWorks. VxWorks is a so-called “RTOS” or Real-Time Operating System. An RTOS is made specifically for real-time applications, that has critical time constraints, or handles events that does. They do this by assigning a hierarchy of priorities. Tasks are then run dependent on which is prioritised the most. To run the low priority tasks aswell, the RTOS can block the higher priority tasks, by delaying it, such that adequate time can be given to other tasks.

The most interesting files I wanted to look at were 68D4, and 40114. This is due to the fact, that these were large LZMA compressed data regions, as we can see from our previous binwalk result. Running file to get information about the type of data residing therein, just yields some sort of “data” for both of these. Trying to open these in Binary Ninja, it auto-registers as mips32. However these standalone “binaries”, don’t really provide much insight, as they’re consequently referring to memory, that is not mapped. This means that we’ll have to find out how to load them together. For this we will write a Binary Ninja loader using their scripting API.

Loading the firmware

What’s a loader?

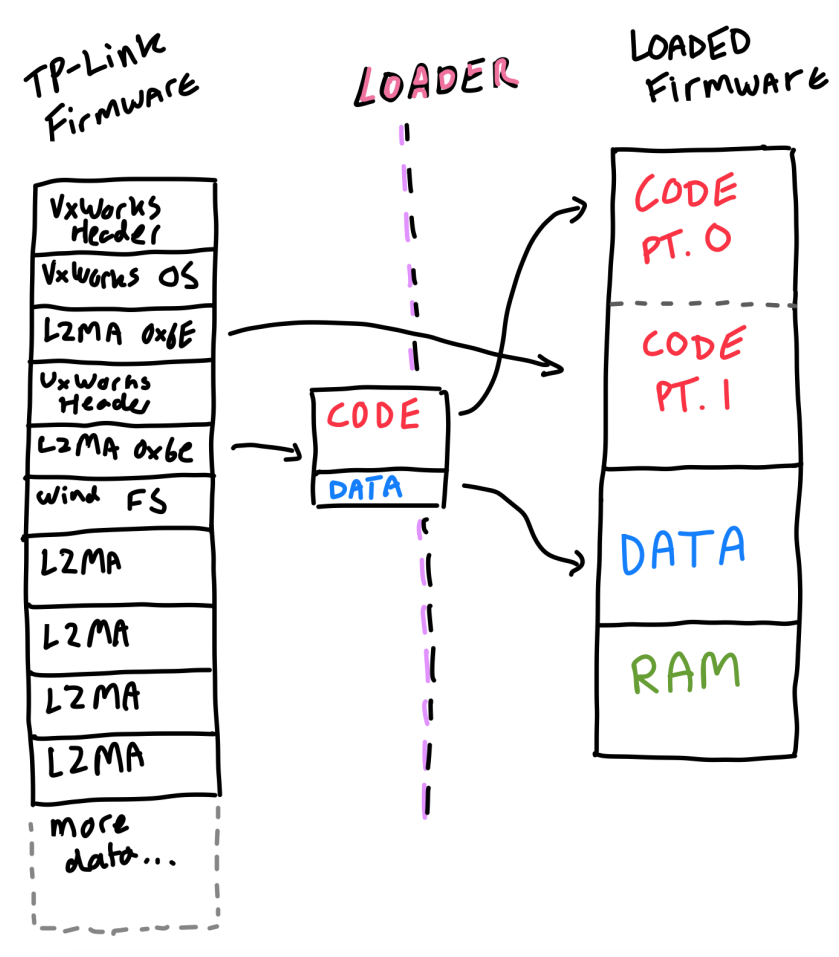

When opening a PE or ELF in a tool like Binary Ninja, the tool needs to figure out what it’s looking at. These file formats are thoroughly documented, and that makes it a lot easier to load them. Regardless, someone still wrote a loader. That’s what we’ll have to do now aswell. The loader will be responsible for mapping specific data offsets into memory as read-write, executable, and so on. We can try visualizing it.

On a high level, that’s what a loader does. We will be decompressing the LZMA archives, and then mapping them appropriately into memory. We need to map the ASCII strings found at the end of a code file to a data section. Then we can try guessing the ram base, but this is not too important.

Requiring information

When requiring information of any kind, we’re used to going to a search engine, to take the first steps. This is no different. I found a fantastic blog post on the Quarkslab blog which I recommend checking out. I was at first a bit discouraged, because the author writes “I conducted a session to search for vulnerabilities but it wasn’t succesful”. Hopefully (wink wink) we’ll find some. From the post, we can see that when the LZMA data is decompressed and loaded into memory, it will be loaded at address 0x80001000. This is also documented in the VxWorks developer manual. Now it’s not the same model, but it is VxWorks also running an Atheros MIPS SOC. We’ll also need to figure out where the other decompressed LZMA archive loads at. To do this I tried to use a tool called binbloom. Binbloom is a super neat tool that can parse a raw binary firmware and determine its loading address, among other features. Running it on the files I was initially surprised to see that the first LZMA archive 68D4, was found to have its base address at 0x80400000. Under that assumption I thought that the second LZMA archive 40114 must be loaded first, at 0x80001000. The fact that the first LZMA loads secondly, is also drawn above. Now I noticed that there was strings in 40114, at offset 0x2c5a30. Now we have our data segment. To clarify, this data section begins at the base address added with said offset from before. Binary Ninja needs to know how large these segments are. We can simply use binwalk for a crude way of checking this. It’ll be done like so:

Binwalk results - determining size

---------------------------------------

26836 0x68D4 <--|

262292 0x40094 <--|---- Subtract size = code0_size

262420 0x40114 <--|

1253300 0x131FB4 <--|---- Subtract size = code1_size

Writing the loader

Using the Binary Ninja API we can write a rudimentary loader. The loader can be seen on my Github, in the TP-Link WR720N repository. We’ll need a LZMADecompressor to decompress the LZMA, and then we need to create our loader class.

# Inherits from the BinaryView class

class TPLinkRTOS(BinaryView):

name = "TPLinkRTOS"

long_name = "TP Link Router RTOS"

def __init__(self, data):

BinaryView.__init__(self, file_metadata=data.file,

parent_view=data) # Initializes a BinaryView

self.raw = data # Get the data, i.e. what's loaded

self.br = BinaryReader(data) # Create BinaryReader

This is the start of the class, and is important for creating our loader. We’ll also make a function to clarify the endianness:

def perform_get_default_endianness(self):

return Endianness.BigEndian

So far we’ve practically just made a glorified file open. We’ll need something utilizing all the neat features of the API. We can begin by using some of the Architectures that they’ve made. That way it will begin trying to look at the data as mips.

# Primary function

def init(self):

self.platform = Architecture["mips32"].standalone_platform

self.arch = Architecture["mips32"]

Now we’re going to handle the data. We start by first decompressing the LZMA archives. We’ll also need to put the decompressed data somewhere, and we’ll put it at the end of the current file.

code0_addr = self.raw.end # Append to end of file

code0_lzma = self.raw.read(code0_begin, size_code0)

code0_data = LZMADecompressor().decompress(code0_lzma)

self.raw.write(code0_addr, code0_data)

There’s not too much more to creating a loader, of course, a lot of syntax has been left out here, but the general principles are simple. To finish we’ll use the add_auto_segment and add_auto_section functions. This step is crucial as we are now allocating memory segments and assigning properties to them such as readability and writability etc.

# Add memory segments to binary view for code0

# add_auto_segment(start: int, length: int, data_offset: int, data_length: int, flags: SegmentFlag)→ None

self.add_auto_segment(code0_base, len(code0_data), code0_addr, len(code0_data), SegmentFlag.SegmentReadable|SegmentFlag.SegmentContainsCode|SegmentFlag.SegmentExecutable)

self.add_auto_section(".code0", code0_base, len(code0_data), SectionSemantics.ReadOnlyCodeSectionSemantics)

# Add memory segments to binary view for code1

self.add_auto_segment(code1_base, code0_base - code1_base, code1_addr, len(code1_data), SegmentFlag.SegmentReadable|SegmentFlag.SegmentContainsCode|SegmentFlag.SegmentExecutable)

code2s_size = 0x2c5a30

self.add_auto_section(".code1", code1_base, code2s_size, SectionSemantics.ReadOnlyCodeSectionSemantics)

# Add data segment to binary view

self.add_auto_section(".data1", data1, code0_base - data1, SectionSemantics.ReadWriteDataSectionSemantics)

self.add_auto_section(".data2", data2, code0_base - data2, SectionSemantics.ReadWriteDataSectionSemantics)

self.add_auto_segment(ram_base, 0x100000, 0, 0, SegmentFlag.SegmentReadable|SegmentFlag.SegmentContainsData|SegmentFlag.SegmentWritable)

self.add_auto_section(".ram", ram_base, 0x100000, SectionSemantics.ReadWriteDataSectionSemantics)

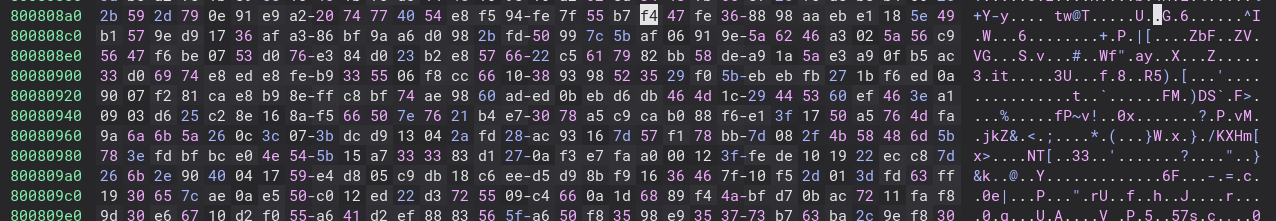

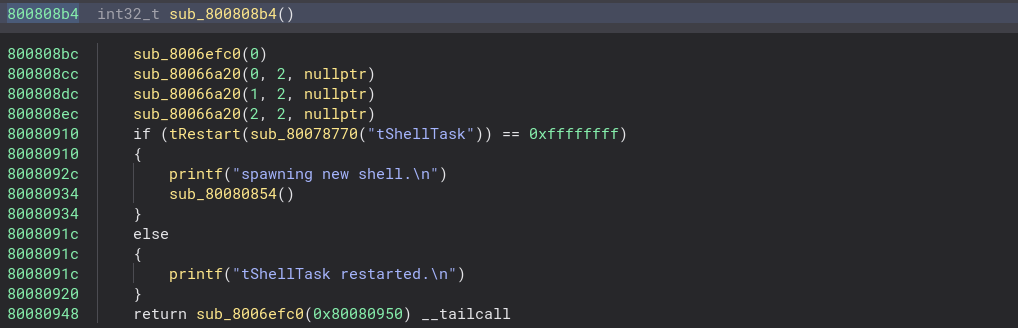

That’s it! We’ve now practically created a loader. The last thing we have to do is register it. Name it __init__.py and place it in /plugins folder. Suddenly we can see code, that properly references itself, and the strings!

Before and after the loader

Before the loader, the binary firmware file, doesn’t give any decompilation or disassembly. It’s simply not able to parse the proprietary file format.

After we’ve made the loader, opening the exact same file, we get proper decompilation, with arguments and string references. We do notice, that we have no symbols, which is a bit tedious - regardless:

Wrapping up

The project is too large to be contained in one post. For that reason I decided to split it into multiple. This part was the initial process, that allowed for getting something to reverse engineer. There’s still lots to go through.

References:

[0]: https://www.tp-link.com/us/support/download/tl-wr720n/v1/#Firmware

[1]: https://deviwiki.com/wiki/Atheros_AR9331

[2]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/VxWorks

[3]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Real-time_operating_system

[4]: https://blog.quarkslab.com/reverse-engineering-a-vxworks-os-based-router.html

[5]: https://github.com/quarkslab/binbloom

[6]: https://github.com/cavetownie

[7]: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Universal_asynchronous_receiver-transmitter

[8]: https://www.uio.no/studier/emner/matnat/fys/FYS4220/h11/undervisningsmateriale/laboppgaver-rt/vxworks_bsp_developers_guide_6.0.pdf [Page: 105]