Preface

In the last post, we looked at the firmware, trying to get something we could analyze. We ended up writing a loader using the Binary Ninja scripting API, and finally getting something to reverse engineer. Now our search for bugs begins. In this post I will be playing around with the routers web UI, and then reverse engineering the firmware searching for bugs.

Bug hunting

Getting the lay of the land

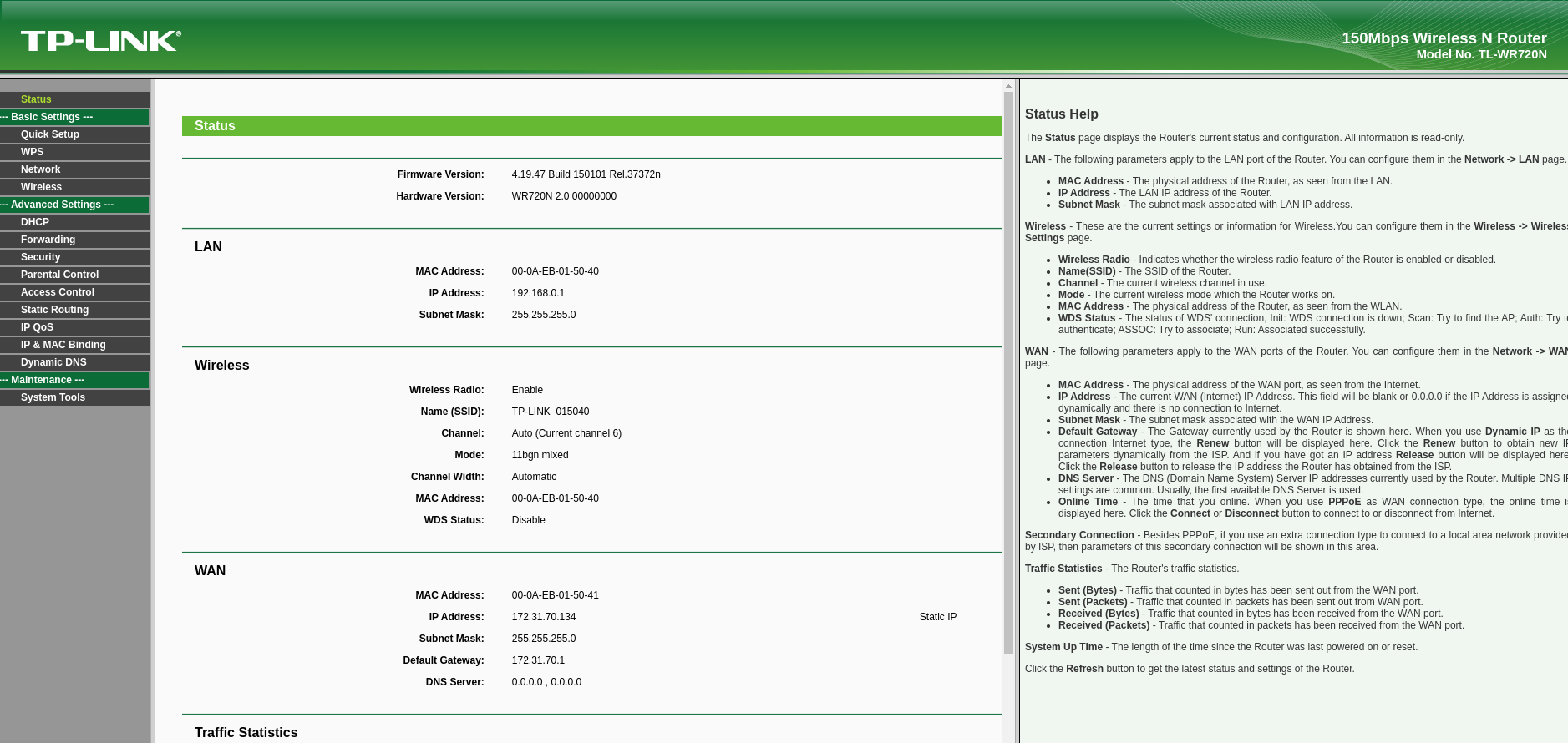

I started by playing around with the webportal, which we concluded in the first post was over at http://192.168.0.1/. Using HTTP Basic Auth, we can log in using the credentials admin:admin, and we’re greeted with a standard web page.

Often the diagnostics tools, are especially interesting. In older routers, and lots of poorly programmed devices, they just insert the command into the commandline, and it is then being executed on the underlying system. We could try command injection - but, we have one big issue. We’re not running Linux, we can’t just run

Often the diagnostics tools, are especially interesting. In older routers, and lots of poorly programmed devices, they just insert the command into the commandline, and it is then being executed on the underlying system. We could try command injection - but, we have one big issue. We’re not running Linux, we can’t just run /bin/bash or any cool commands - So what do we do? However I still didn’t want to give up testing the ping functionality, so I went and manually fuzzed that first.

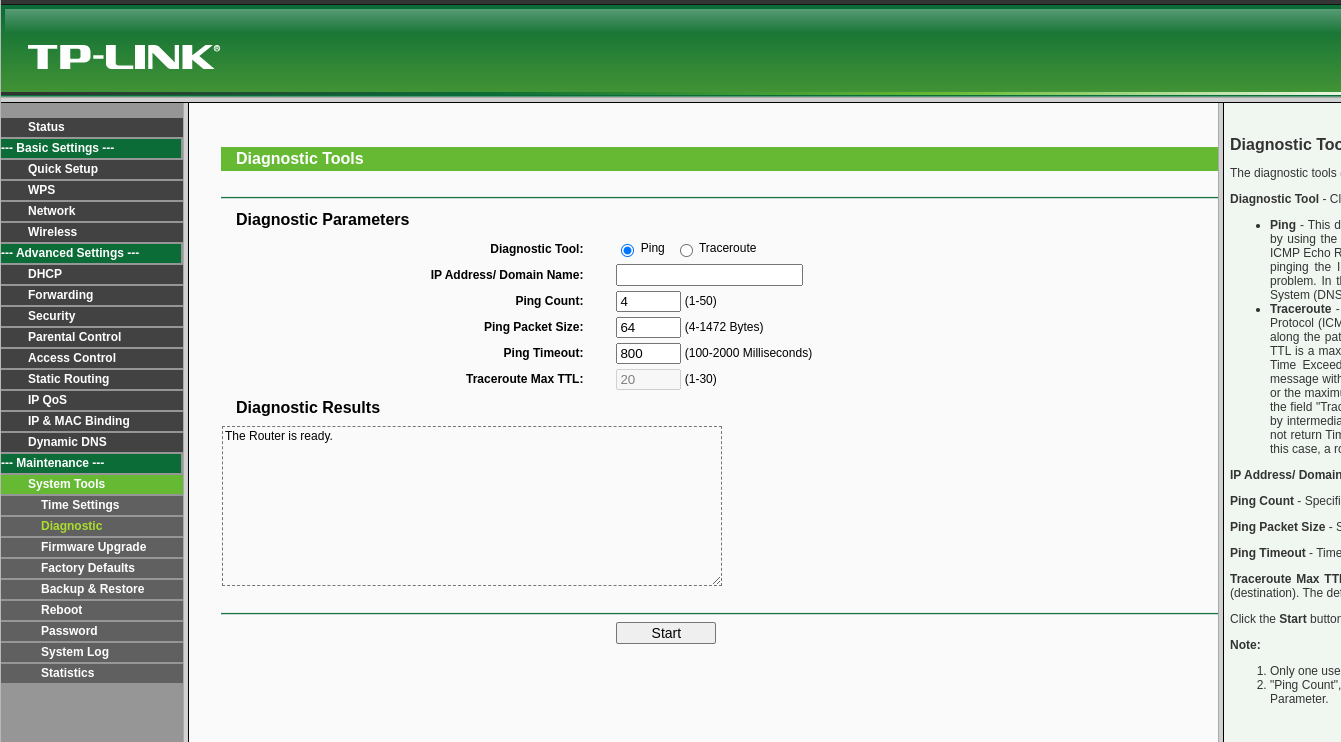

We have a ping count, a packet size, and a timeout. We can also use the traceroute tool. Manually messing with it, putting

We have a ping count, a packet size, and a timeout. We can also use the traceroute tool. Manually messing with it, putting %s, %1000$s, trying to get a crash, didn’t work. User input was limited, and I could not put in packet sizes over 1472 or below 4. However these checks are only made in the frontend. This means that we can intercept the request, just after the frontend has approved the request, and then change it there. We can use a tool like Burp Suite for this. After testing a few different things, I noticed something weird. I wasn’t getting any responses in Burp anymore. I tried pinging the device from my own host, and it said host unreachable. After a bit of debugging I found out I had found the first bug, a DOS (Denial-of-Service). This was done so, changing the packet size to a really large number. Below the very simple PoC can be seen. We’ll see exactly where in the code, this is triggered later, to see if we can exploit it.

###

# PoC - Ping DOS (TP-LINK WR720N)

###

from pwn import *

io = remote("192.168.0.1", 80)

req = b"""GET /userRpm/PingIframeRpm.htm?ping_addr=127.0.0.1&doType=ping&isNew=new&sendNum=4&pSize=132323232&overTime=800&trHops=20 HTTP/1.1\r

Host: 192.168.0.1\r

Authorization: Basic YWRtaW46YWRtaW4=\r

Connection: close\r\n\r\n"""

io.send(req)

io.interactive()

Reversing the firmware, and discovering the cause

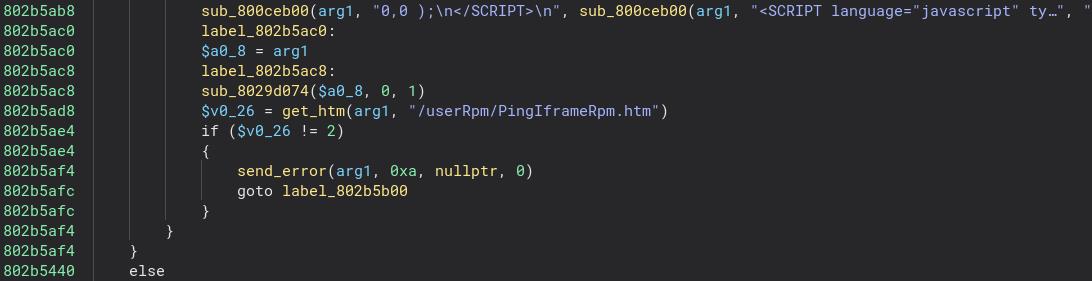

We’re making a GET request to the endpoint /userRPM/PingIframeRpm.htm. This is going to be present in the code somewhere. We’ll try looking for strings that contain this in Binary Ninja.

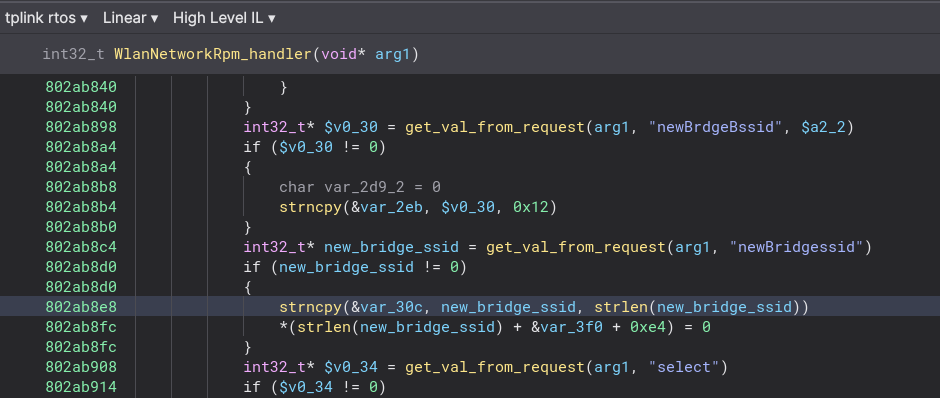

We’ve now found an interesting part. We want to figure out how this relates to the ping functionality. The screenshot is at the end of the function, and above the code in the screenshot, there’s a lot more to analyze. We’re now looking for strings that correspond to the parameters, i.e. pSize. I found a function that matches this. I’ll call it get_val_from_request. A small note here is, that if we ever wanted to write a fuzzer for the router. We could use this function and the references to it, to find possible HTTP parameters.

Cool! Let’s look at some different parts of the code, to see if we can get a better general understanding of the code. I found a bunch of strings that all had

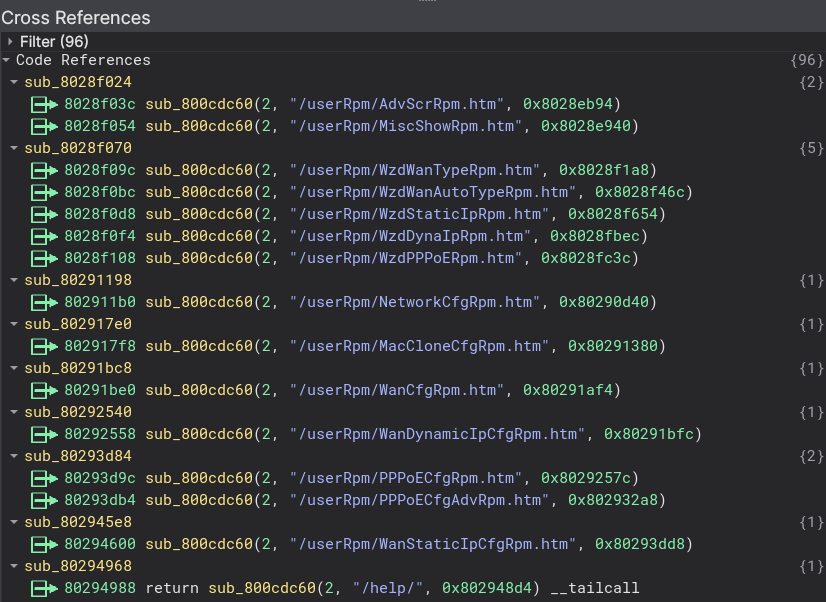

Cool! Let’s look at some different parts of the code, to see if we can get a better general understanding of the code. I found a bunch of strings that all had /userRpm/SITE.htm, where site is a specific endpoint. These were consequently refered to by a specific function. This is probably the handler of these htm sites. This function at 0x800cdc60, has a pointer as the third argument, that relates directly to the second argument. The third argument doesn’t have a function name, we’re going to script us out of this, so that we don’t have to manually rename all the functions. Prior to renaming:  We’re going to get the references to the function

We’re going to get the references to the function 0x800cdc60, we can do this using bv.get_code_refs, which will give us an iterator of references to that function. We can then get the second and third argument to the function, and rename the function of the called function. It’s really simple, and will make the reversing a lot easier!

###

# Find webpage handlers, and rename them appropriately

# TL-WR720N

###

from binaryninja import *

page_handler_refs = bv.get_code_refs(0x800cdc60)

for func in page_handler_refs:

# Example: sub_800cdc60(2, "/userRpm/WanStaticIpCfgRpm.htm", 0x80293dd8)

addr_of_str = func.function.get_parameter_at(func.address, None, 1).value

addr_of_called = func.function.get_parameter_at(func.address, None, 2).value

str_val = bv.get_string_at(addr_of_str).value

val = str_val.replace("/userRpm/", "")

val = val.replace(".htm", "")

called = bv.get_function_at(addr_of_called)

# Change name

called.name = val + "_handler"

And after running it, we’ll now see some code that is way easier to read. We’ve actually just avoided renaming 96 functions manually, that’s a win in my book.

The ping bug

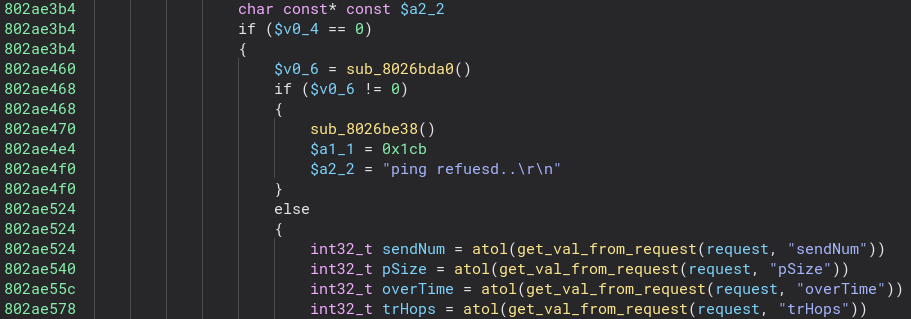

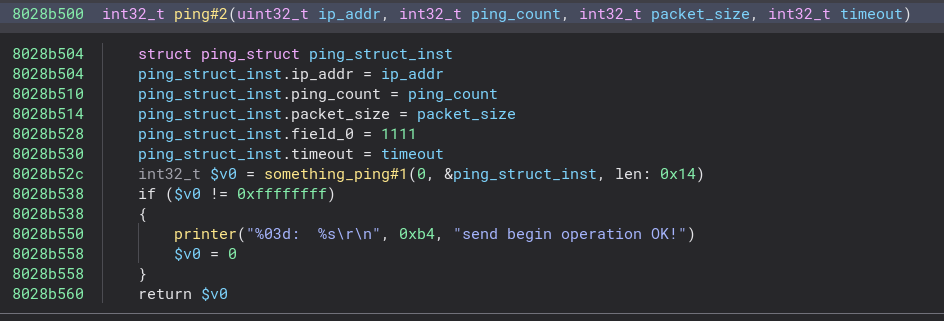

Now this would be a great time to hook up to UART, but this was right during christmas, and I had no UART. We’ll need to find the ping functionality ourselves. It took some time, but I managed to find the relevant function. The function used a struct for the data relevant to the ping functionality, and after I had figured out how that looked like, the code looked like this:

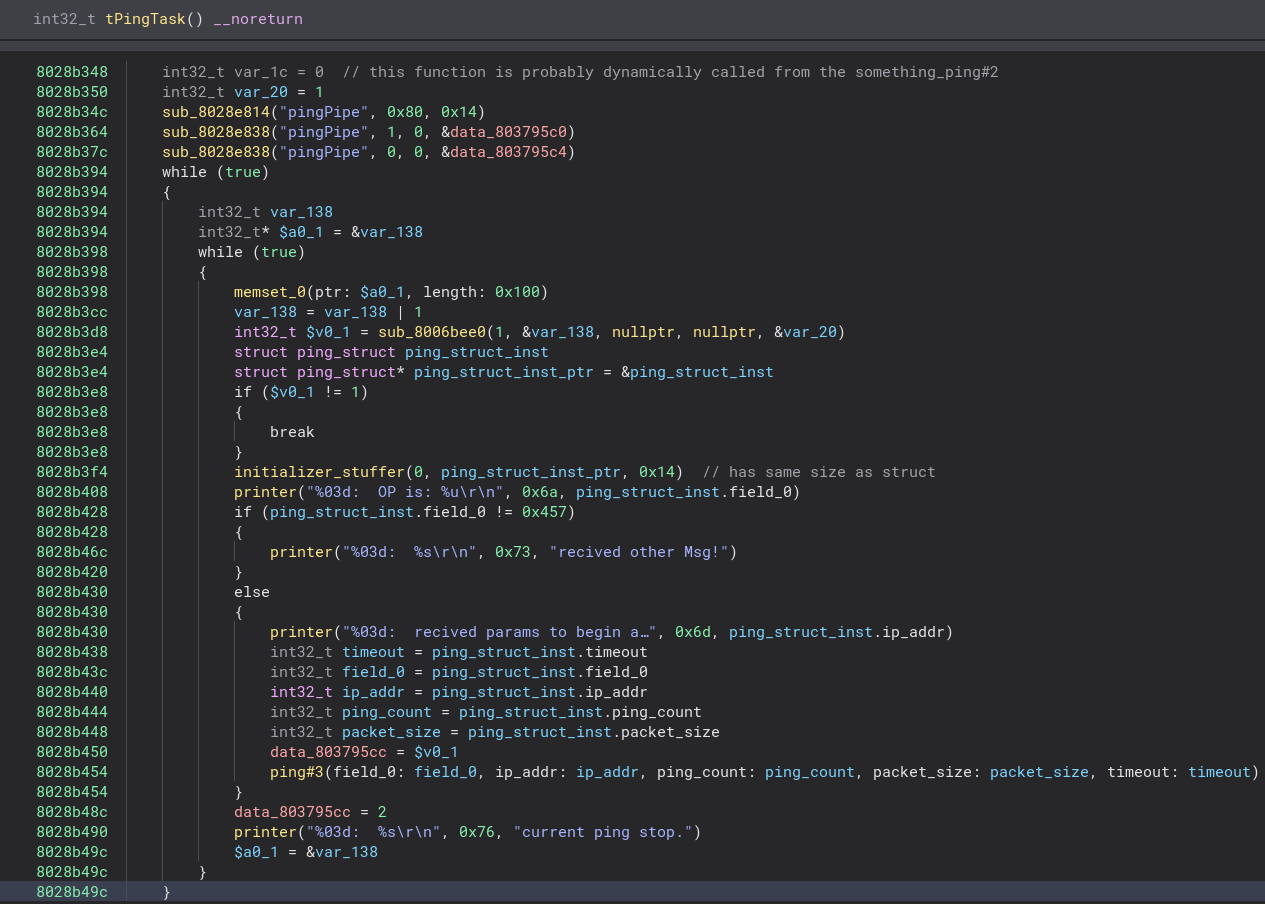

Now somehow it ends up calling tPingTask, which is a VxWorks specific task. It wasn’t apparent to me how this call happens, but due to the fact that this is in the same task, the stack and registers are shared. This is documented in the VxWorks5.5.1 manual, section 2.2 VxWorks Tasks. The reason I believe that is important is because it could explain why the ping struct somehow is transfered, as it looks to me as it’s uninitialized in tPingTask.

Now somehow it ends up calling tPingTask, which is a VxWorks specific task. It wasn’t apparent to me how this call happens, but due to the fact that this is in the same task, the stack and registers are shared. This is documented in the VxWorks5.5.1 manual, section 2.2 VxWorks Tasks. The reason I believe that is important is because it could explain why the ping struct somehow is transfered, as it looks to me as it’s uninitialized in tPingTask.

We see that it just sets up

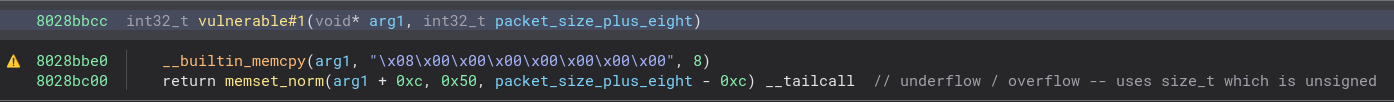

We see that it just sets up received params to begin a.., and then finally calls ping#3. Quite a few layers. Let’s look at the ping#3. Remembering that we know the bug is triggered by the packet size being large, so we want to look at places where it’s being used. Quickly we find the root cause:

We see that it’s taking our size, turning it into an unsigned integer, and using it for memset - into

We see that it’s taking our size, turning it into an unsigned integer, and using it for memset - into arg1 + 0xc, which is a stack buffer with a static size. However the bad news for us is, that it’s using the fixed data of 0x50. This means, we can’t leverage this for an exploit. Actually this DOS, was assigned CVE-2023-24361, however that’s not the title of the post, is it?:)

Looking for other bugs

When looking for bugs, it’s exciting to look at functions, that manages user input, in some way. Some of these include strcpy, strncpy, gets, free, malloc, gets, fgets, memcpy, memmove, memset. These are often sinners, so we’ll look for these. The binary doesn’t have symbols, so I spent some time looking for the strlen function, which I ended up finding:

80062900 char* $a1 = &arg1[1]

80062908 char* $v1 = $a1

80062910 while (true)

80062910 {

80062910 uint32_t $v0_1 = zx.d(*arg1)

80062918 arg1 = $v1

80062914 if ($v0_1 == 0)

80062914 {

80062914 break

80062914 }

8006290c $v1 = &$v1[1]

8006290c }

8006291c return $v1 - $a1

The function above is the strlen functionality in our firmware. It gets the first argument, and begins iterating through it starting from the second character (1-indexing), and then keeps going till it hits a null byte. When it does, it returns the difference between that ptr, and the ptr of the first character. This is to avoid including the null byte in the strlen. From the man page:

DESCRIPTION

The strlen() function calculates the length of the string pointed to by s, excluding the terminating null byte

('\0').

This in itself is not too interesting, as this only maintains sizes, and doesn’t move user input. I spent some more time reversing and found the strncpy at 0x80062990. Looking for strncpy’s that use strlen, we see a few. Specifically one stuck out:

We see that it takes a value from a request, and then copies that into a buffer

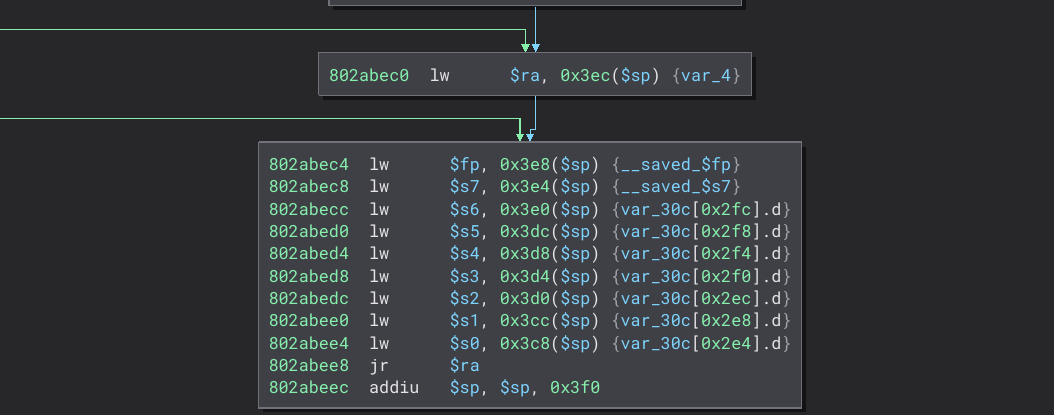

We see that it takes a value from a request, and then copies that into a buffer var_30c. So we effectively seem to have a stack based buffer overflow here. Now turning the buffer into a char buffer we can easily see how many bytes we need to be able to do Return-Oriented-Programming or ROP. We see that if we send 0x2e4-0x4, we’ll have overwritten the $ra register which is jumped to. That means we have to send a padding of 0x2e4-0x4-0x4 and then a four-byte address, to ROP. Debugging this will be hard without UART - so we need UART.

After finding this, I realized that a vulnerability like it had been reported before, however only on non-RTOS TP-Link routers, that is, Linux routers. Now the consequence of this could be remote code execution. Trying to ROP seemed to do nothing however. Interesting?

After finding this, I realized that a vulnerability like it had been reported before, however only on non-RTOS TP-Link routers, that is, Linux routers. Now the consequence of this could be remote code execution. Trying to ROP seemed to do nothing however. Interesting?

Wrapping up

This time we reversed the firmware, recovered some symbols, and found a few bugs. Next post we will finally get UART, find out why we couldn’t ROP, fix that, and finally give a small proof of concept script to show that getting code execution is possible.